Wien

Pronounced "Veen" (English: Vienna)

The earliest known Jewish settlers arrived in Vienna in the 1100s, but were unable to maintain a permanent community due to persecution and murders during the Crusades, the Black Plague and other periods of oppression.

From the 1430s Vienna served as the seat of the Habsburg dynasty that ruled Central Europe until the early 1900s. Depending on the ruler, Jews experienced periods of great toleration. In 1782 Emperor Joseph II issued the Edict of Tolerance that lifted many of the previous restrictions on Jewish life.

The Edict enabled the Jews of Vienna to deepen their religious, educational, social and political activity within the existing Jewish community and to create the infrastructure to support it through the establishment of temples and synagogues, Jewish schools and seminaries, museums, libraries and social welfare agencies.

The Jewish population of Vienna increased dramatically, from about 3,700 in 1846 to more than 118,000 by 1890. A number of important thinkers of Jewish origin made their home in the city, including Theodor Herzl, Gustav Mahler, Arthur Schoenberg and Sigmund Freud.

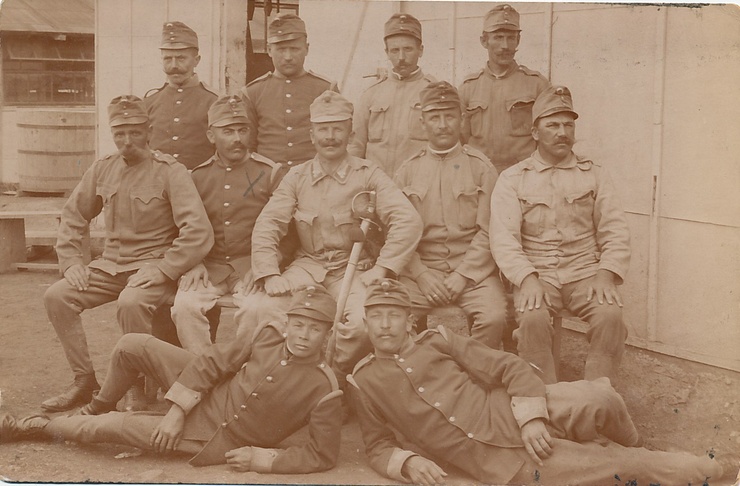

During World War I (1914-1918) Jewish citizens fought and died for the Austrian Empire alongside their Christian neighbors. Survivors Lily Stark, Charles Kurt and Hermann Rath recalled how their fathers served in the Austrian Army. Rath said, “My father, in his army uniform, used to come to kindergarten to pick me up when he was on leave.”

After the war Austria was established as an independent country. The Jewish population of Vienna continued to grow, reaching its peak in 1923, with more than 200,000 Jewish residents in a city of almost two million.

Many Jews held professional positions. Survivor Luisa Kopinsky said, “My mother was an attorney...and my father was a banker.” Others labored in unskilled jobs. Rath recalled his family’s “hand-knitting operation,” saying, “We had to work to support the family, which we did since I was probably bar-mitzvahed at the age of 13.”

By the mid-1930s Vienna boasted 19 temples and 63 smaller houses of prayer. Charles Kurt recalled, “I remember distinctly that in that temple the women were on one side and the men were on the other side. It was a very, very beautiful temple on the inside.” Lily Stark said, “We were observing all the holidays very strictly.”

Fini Konstat and other survivors also recalled that Jewish religious instruction was included in their public-school curriculum. Outside of school, these survivors and their families participated in organizations such as the Chevra Kaddisha burial society, Hakoah sports club and Zionist Betar organization.

After Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of neighboring Germany in 1933, the Jews of the Vienna became the targets of intensifying persecution. Lily Stark recalled an antisemitic group “started to rough us up” as she was leaving a meeting of her youth club. Fred Stark remembered, “I had brawls in school” and Hermann Rath recalled that Jews were ordered out of lecture halls and laboratories, where “they would beat us to a pulp.”

After Austria was incorporated into Germany during the Anschluss of March 1938, leaders of the Jewish community were arrested, the Chief Rabbi of the city was forced to sweep the street with his bare hands, and prominent Jews were robbed of their property and sent to Dachau. Survivor Ilse Marcks said, “They went to the synagogue, they took out the scrolls, and tore them up, and then made the Jewish men urinate on them.”

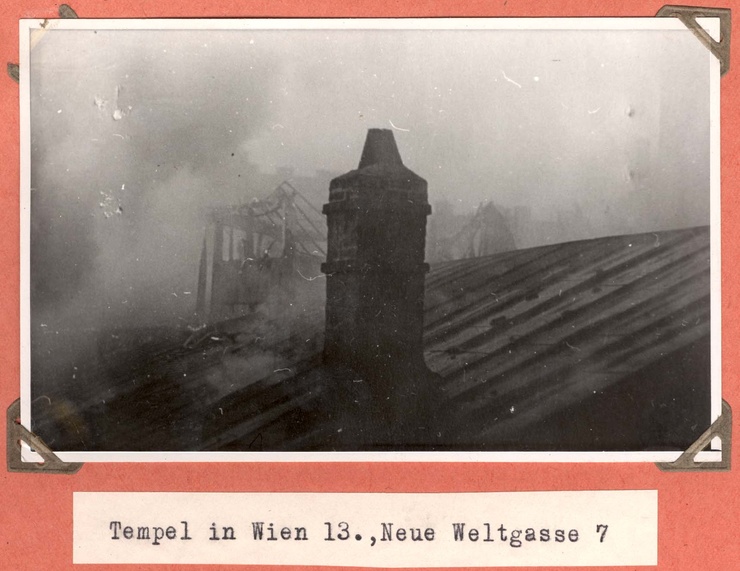

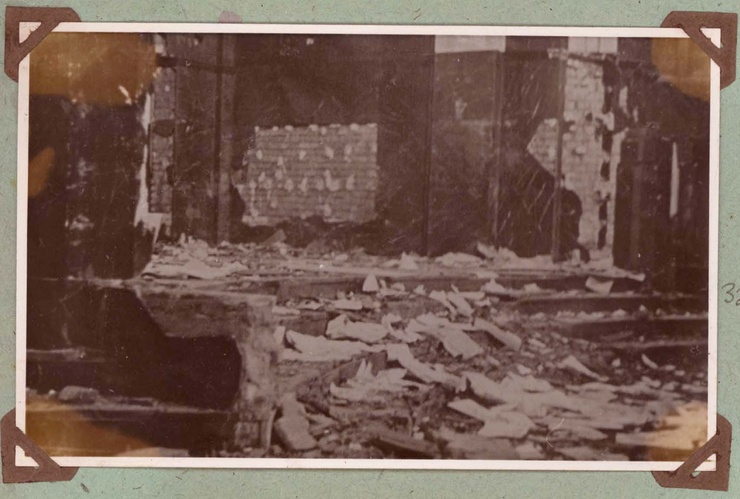

During the night of Kristallnacht in November 1939, 42 synagogues were burned, about 4,000 Jewish stores were looted, Jewish homes were broken into and thousands of Jews were arrested. Survivor Hans Peter Katz described how his father’s store was “pilfered, destroyed.” Charles Kurt remembered, “The street was an absolute sight. There were fixtures on the street. There were groceries on the street. There was glass, more glass, and more glass.”

Many Jews fled and by the end of 1939 only about 50,000 were left in the city. Of those that remained approximately 43,000 were deported to ghettoes in Eastern Europe, and finally to concentration camps.

In September 1942 the last mass transport of Jews left Vienna and in November the Jewish community was officially dissolved. More than 240 years of Jewish cultural life in Vienna was destroyed.

Wien: Photographs & Artifacts

-

Rudolf Kohn (second row, second from left) fought for the Austrian army in World War I (1914-1918). Photo courtesy of Yvette Pintar

Rudolf Kohn (second row, second from left) fought for the Austrian army in World War I (1914-1918). Photo courtesy of Yvette Pintar -

Jewish soldiers in a synagogue in Vienna, World War I. Credit: Yad Vashem

Jewish soldiers in a synagogue in Vienna, World War I. Credit: Yad Vashem -

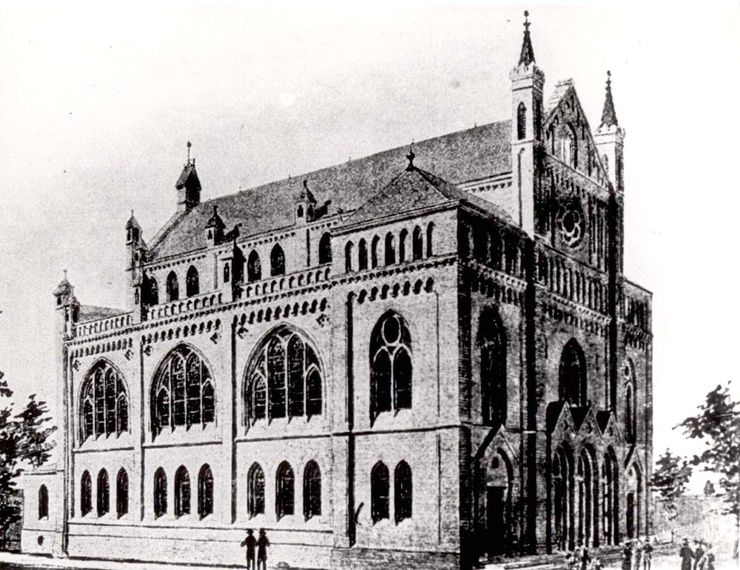

Exterior of a synagogue in Vienna. Credit: Yad Vashem

Exterior of a synagogue in Vienna. Credit: Yad Vashem -

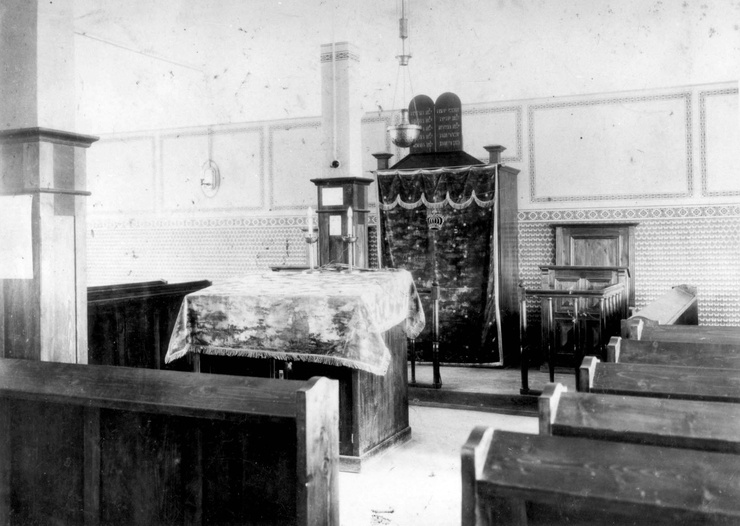

Interior of a synagogue in Vienna, prewar. Credit: Yad Vashem

Interior of a synagogue in Vienna, prewar. Credit: Yad Vashem -

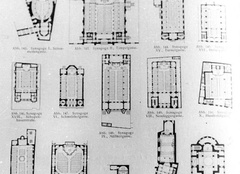

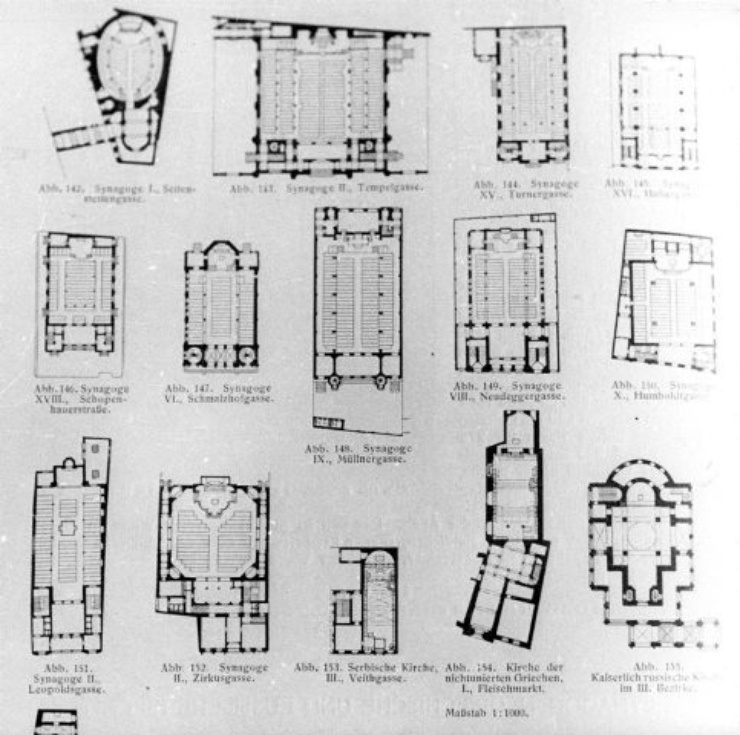

Sketches of synagogues in Vienna. Credit: Yad Vashem

Sketches of synagogues in Vienna. Credit: Yad Vashem -

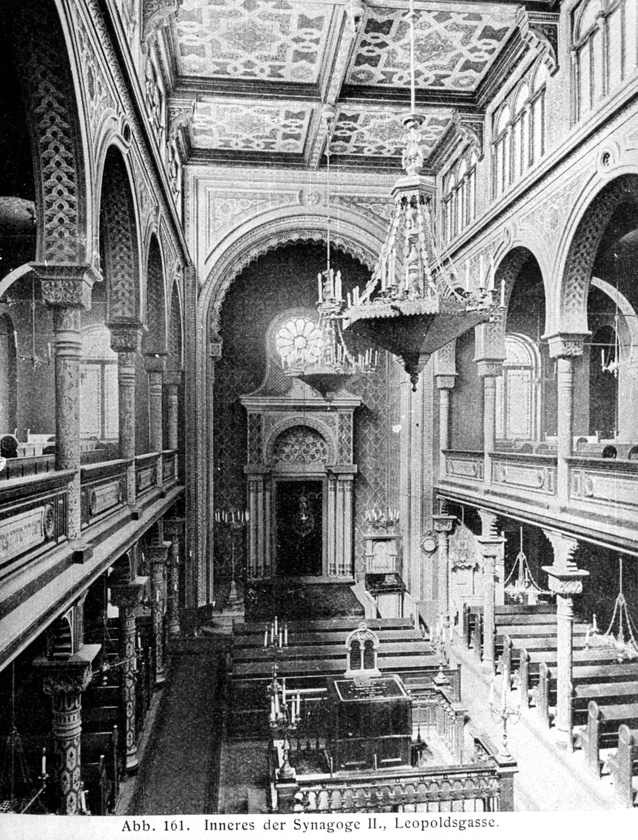

Inside a synagogue on Leopoldsgasse Street in Vienna. Credit: Yad Vashem

Inside a synagogue on Leopoldsgasse Street in Vienna. Credit: Yad Vashem -

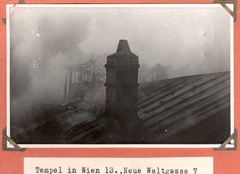

A synagogue at 7 Neue Weltgasse, Vienna in flames during Kristallnacht, November 1938. Credit: Yad Vashem

A synagogue at 7 Neue Weltgasse, Vienna in flames during Kristallnacht, November 1938. Credit: Yad Vashem -

A photograph of the Great Synagogue on Graz St. in Vienna, before the war

A photograph of the Great Synagogue on Graz St. in Vienna, before the war -

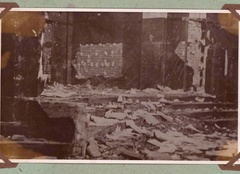

The interior of the "Beit Tahara" (where the dead are prepared for burial) in a Jewish cemetery in Vienna, after Kristallnacht (November 9-10, 1938). Credit: Yad Vashem

The interior of the "Beit Tahara" (where the dead are prepared for burial) in a Jewish cemetery in Vienna, after Kristallnacht (November 9-10, 1938). Credit: Yad Vashem -

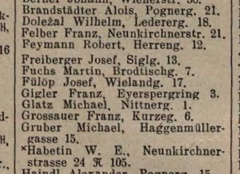

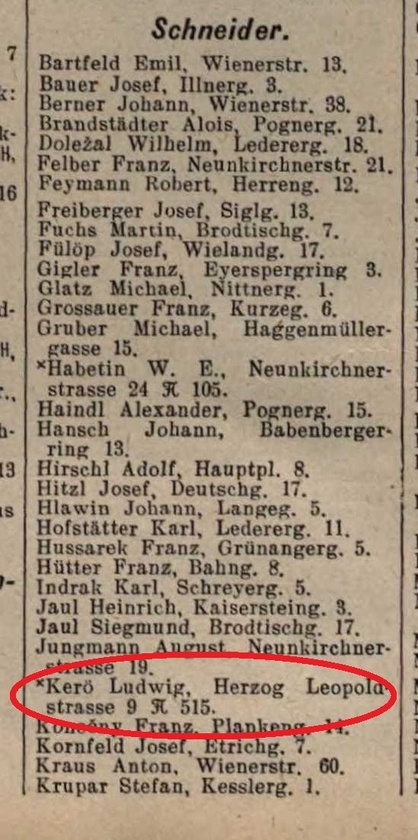

This directory listing shows that Ludwig Kerö worked as a tailor in Vienna. Ludwig committed suicide in February 1939, but his daughter Helga was able to immigrate to the United States. Photo courtesy of Yvette Pintar

This directory listing shows that Ludwig Kerö worked as a tailor in Vienna. Ludwig committed suicide in February 1939, but his daughter Helga was able to immigrate to the United States. Photo courtesy of Yvette Pintar

Destroyed Communities Memorial Slope

Wien: Survivors

Life was so good – gemütlich – that nobody seemed to see the danger or care.

When Hitler came into power, I was very happy. I even said, ‘Heil Hitler.’ I didn’t know what I was talking about. And all of a sudden, all of our friends in the building, who were friends, Gentile—they turned against us, and we were thrown out by one of our friends.

Much has been said about the Holocaust consciousness raising, and I agree that one of the things we can do—and that is why I am here—to stand up and be counted as being against something like that ever being permitted to happen again.

I still see it in front of me: the first week of the German arrival in Vienna and from that fourth floor window in this apartment building, I remember Hitler’s triumphant arrival in Vienna because first came the tanks, then came the Mercedes with him standing next to the driver, his left hand on the windshield and his right hand giving the Hitler salute. It’s hard to describe how these people acted when this man arrived on the scene, the immense welcome the people of Vienna gave Hitler.

There was this horrible, dank and damp, miserable weather and this railroad station was dark and all these children and parents crying. In fact, ninety percent of the parents were not reunited with their children.

It was, I would say, an average childhood. In the summer we went on vacation to the mountains and went ice skating for recreation. And things were just normal until the Germans entered Austria.

One evening in early August 1938, I had to say my heart-rending goodbyes to my parents, to Eli and Otto, not knowing if and when we were to see each other again. However, as hard as it was to leave, there was also this strong feeling of hope.

It was a religious family, yes. My father was very religious and dedicated all his life for the community center, and for the poor people.

There was this little Christian girl who one day on leaving the office… She had never spoken to me and she said, ‘Don’t go through this street when you leave here. They are taking Jews to do the washing of the sidewalk. Try and take another route,’ and she was right.

Hugo Steinfink was born on May 22, 1924 in Vienna, Austria.