Chrzanow

Pronounced "Kh-ZHAHN-oov"

Jewish settlement of Chrzanów began in the 1700s. The town’s first synagogue opened in 1745, a wooden structure that was replaced by a more permanent brick building in 1786. A Jewish cemetery opened in 1759 and by 1765 Chrzanów was home to 60 Jewish families (327 people).

In 1795 Chrzanów became part of the Austrian Empire. Jewish merchants prospered from the town’s proximity to the “Three Emperors’ Corner” where the borders of the Russian, Prussian, and Austrian Empires met.

From 1888 to 1920 Jews held an absolute majority in the town council and in 1900 numbered more than half of Chrzanów’s total population (5,504 of 10,193 residents). From 1899 to 1912 the city boasted a Jewish mayor, the lawyer Dr. Zygmunt Keppler. Prominent Jewish citizen Henryk Lowenfeld donated the city’s landscaped boulevard, as well as funds for a library with books in Hebrew, Yiddish, Polish and German.

Like their neighbors, the Jews of Chrzanów fought and died fighting for the Austrian Empire during World War I (1914-1918). In 1919, Chrzanów became part of the Republic of Poland.

Survivor David Wachsberg remembered from his childhood in the 1920s, “It was a Jewish town. A lot of yeshivas [schools to study Jewish scripture], synagogues, one church. Two public schools, big buildings.” Wachsberg continued, “It was a county seat and it was a beautiful city,” adding, “even in those days, in my young memories, Jews and Gentiles lived closely together.”

The family of Survivors Sigmund, Sol and Max Jucker owned the same bakery in the town for 200 years. Sigmund recalled, “I was already helping at home in the bakery when I was 10 years old.” He continued, “We weren’t rich, but we had everything we needed.” Like other Jewish children in Chrzanów, Sigmund Jucker attended a cheder elementary school for religious instruction.

David Wachsberg remembered the Orthodox synagogue he and his family attended, saying, “We had one of the most beautiful synagogues.” He recalled, “Five- or six-thousand people went there. On the bottom were men, on the top were the ladies.” At home, Wachsberg said, “I remember my daddy putting on everyday tefillin [prayer boxes].” His sister Ann Blum (née Wachsberg) added, “Life was based on so much love and respect.”

The end of the World War I and rising Polish nationalism also meant the growth of antisemitic violence. On October 5, 1918, Jewish stores were broken into and their merchandise looted. Antisemitic gangs began to harass Jews on the street, sometimes cutting off their beards, or breaking into study houses and beating up students. Sigmund Jucker remembered, “The church in our town was making such a hate. ‘Don’t buy from Jews,’ and ‘The Jews did that.’”

The violence continued through the 1930s, for example when the Jewish cemetery was vandalized in 1934. The antisemitic National Democracy party gained influence in Poland, especially among younger generations. Wachsberg described his memory of one pogrom, saying, “You went the whole town through—windows broken, stones thrown in.”

Jucker recalled that just prior to World War II his family “built a new house, with a new bakery. We moved into it and we didn’t live in it too long because the war broke out in 1939.” As with so many others, this thriving community was destroyed after the Nazi invasion of Poland in September 1939.

Chrzanow: Photographs & Artifacts

-

The main market square in Chrzanów, circa 1910. Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

The main market square in Chrzanów, circa 1910. Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain -

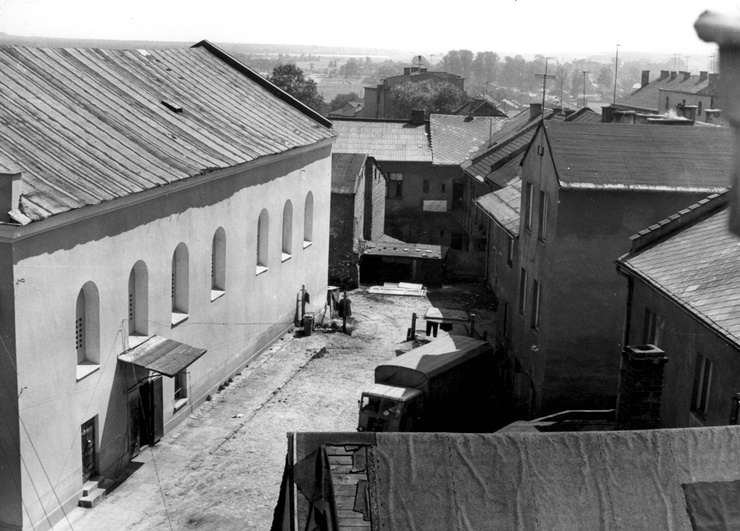

Exterior of a synagogue in Chrzanów. Credit: Yad Vashem

Exterior of a synagogue in Chrzanów. Credit: Yad Vashem -

Exterior of a synagogue in Chrzanów. Credit: Yad Vashem

Exterior of a synagogue in Chrzanów. Credit: Yad Vashem -

Group portrait of a Jewish kindergarten class in Chrzanow, circa 1929-1931. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Mali Lamm Baruch

Group portrait of a Jewish kindergarten class in Chrzanow, circa 1929-1931. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Mali Lamm Baruch -

Gravestones in the Jewish cemetery in Chrzanów, postwar. Credit: Yad Vashem

Gravestones in the Jewish cemetery in Chrzanów, postwar. Credit: Yad Vashem -

Gravestones in the Jewish cemetery, postwar. Credit: Yad Vashem

Gravestones in the Jewish cemetery, postwar. Credit: Yad Vashem -

The Jewish cemetery in Chrzanów, December 2007. Credit: sztetl.org.pl/Małgorzata Płoszaj

The Jewish cemetery in Chrzanów, December 2007. Credit: sztetl.org.pl/Małgorzata Płoszaj -

Aleja Henryka, or "Henryk's Avenue," was named for prominent Jewish citizen Henryk Lowenfeld. This photo was taken in 2004. © Mariusz Paździora / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-3.0

Aleja Henryka, or "Henryk's Avenue," was named for prominent Jewish citizen Henryk Lowenfeld. This photo was taken in 2004. © Mariusz Paździora / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-3.0

Destroyed Communities Memorial Slope

Chrzanow: Survivors

I remember the big tanks going down the street, and I was such a little girl and I used to be so scared, these tanks, they make so much noise, the big trucks full of German soldiers, and the big tanks just keep roaring and roaring and roaring, and I used to hide behind my father. He was this giant in my eyes, you know. If I was near him nothing could happen.

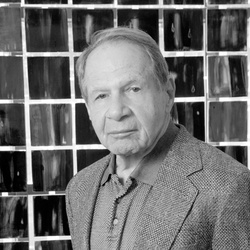

Wolf Brauner was born in Chrzanów, Poland on July 21, 1920.

We weren’t rich, but we had everything we needed and life was going on. We built a new house, with a new bakery, in 1938. We moved into it and we didn’t live in it too long because the war broke out in 1939.

It was a kosher home, a religious home. I remember my daddy putting on everyday tefilllin [prayer boxes].

After the German invasion, we children couldn’t even go out of the house. When we didn’t work, we stayed right in the yard in front of the house, never moved away 100 or 200 yards into the street. The total life has changed. There was no Saturday, there was no Friday, there was no nothing. There was nothing.