Brno

Pronounced "BR-noh" (German: Brünn)

The earliest known Jewish settlers came to Brno in the 1200s, where they were granted many rights not often extended in the Medieval world. These included protection of life and property, as well as the elimination of restrictions on the jobs Jews were allowed to hold. However, Jews were also charged an extra tax: 25 percent of what it cost to maintain the city’s fortifications.

Almost 100 years later in 1345, King Charles IV issued a charter encouraging Jewish settlement. Records indicate a Jewish Quarter of Brno with a “Jews’ Gate” into that part of the city. The earliest known Jewish tombstone from this period is dated 1373.

Sadly this early Jewish community was expelled from Brno in 1454. Jewish life in the city all but disappeared until a new community gradually began to develop in the late 1700s and 1800s beginning with merchants who came to trade in the city’s fairs. An inn for Jewish travelers opened in 1724, and in 1769 Jews were permitted to hold religious services in private homes. However, in 1812 authorities imposed an additional tax for “keeping a Torah.”

It was not until 1848 that Jews were officially permitted to reside within the city. The Jewish cemetery was consecrated just a few years later in 1852, followed by the large Maior synagogue in 1855. In 1859 the Jewish community of Brno gained official recognition and a Jewish school opened in 1861. As the community grew, two new synagogues were built in 1883 and 1906.

By the late 1800s several Jewish industrialists had helped contribute to economic developments that earned Brno the nickname “Manchester of the East.” As more and more Jews moved from smaller towns and villages into the city, multiple institutions were founded to serve the community’s needs. These included the B’nai B’rith lodge (founded in 1895), the Jewish “People’s Voice” weekly newspaper (founded in 1902), a number of Zionist groups and Maccabiah (sport) organizations.

The Jews of Brno fought for the Austrian Empire during World War I (1914-1918) alongside their non-Jewish neighbors. Survivor John Haenosh said, “My uncle, the brother of my father, died as a soldier for the Austrian army.” About 16,000 Jewish refugees came to Brno from Eastern Europe seeking refuge from the conflict.

In 1918 the city became part of the newly established country of Czechoslovakia. Haenosh remembered growing up in an environment where Jews were highly integrated into the life of the city, saying, “I had many, many non-Jewish friends.” Survivor Liana Ornstein added, “I don’t remember ever feeling persecuted before the Germans walked in.”

The families of Haenosh and Ornstein were also involved in the city’s thriving cloth industry. Ornstein remembered, “My father was a textile specialist. He was director of the mill.” While Haenosh attended a Jewish school that he remembered was “very religious,” Liana Ornstein attended a public school. Ornstein recalled that “when I went to Czech school I had Bible class,” though her family still attended synagogue on Jewish holidays.

From 1929 until 1938 a Jewish doctor of law, Ludwig Czech, served as a minister in the country’s democratic government. However, this government was dissolved after the Munich Agreement of September 1938 that allowed Hitler’s Nazi regime to take over the country. Dr. Ludwig Czech was one of about 10,000 Jews deported from the city and sent to concentration camps from 1941 to 1942. Only 674 members of the once-thriving community of Brno are known to have survived the Holocaust.

Brno: Photographs & Artifacts

-

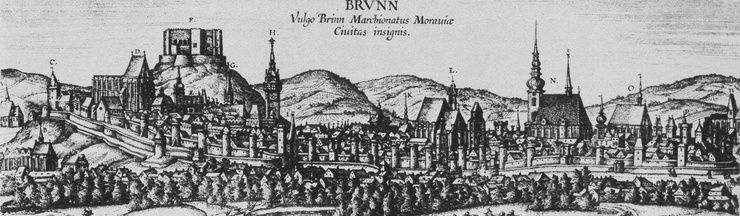

The city of Brno in 1617. Georg Houfnagel / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain (PD-1996)

The city of Brno in 1617. Georg Houfnagel / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain (PD-1996) -

Holy ark in a synagogue in Brno, prewar. Credit: Yad Vashem

Holy ark in a synagogue in Brno, prewar. Credit: Yad Vashem -

The inner wall of the Great Synagogue in Brno that was destroyed in 1939. Credit: Yad Vashem

The inner wall of the Great Synagogue in Brno that was destroyed in 1939. Credit: Yad Vashem -

Two Orthodox Jewish men visit a spa in Czechoslovakia. Pictured on the left is Rabbi Elias Grunfeld, the chief rabbi of Brno. He later perished in the Holocaust. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Malvina Burstein

Two Orthodox Jewish men visit a spa in Czechoslovakia. Pictured on the left is Rabbi Elias Grunfeld, the chief rabbi of Brno. He later perished in the Holocaust. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Malvina Burstein -

A professional school in Brno, 1940. Credit: Yad Vashem

A professional school in Brno, 1940. Credit: Yad Vashem

Destroyed Communities Memorial Slope

Brno: Survivors

I must say that most of the older generation, the generation of my father, didn’t believe it [persecution of Jews in Germany] could be true. They said, ‘Those things are being exaggerated.’ And my father was of the opinion, he has no enemies, and something like this could never happen to him. And he wasn’t the only one; most of the Jews in Czechoslovakia were of this opinion.

I don’t remember ever feeling persecuted before the Germans walked in.