Bruxelles

(French: Bruxelles, Dutch: Brussel, German: Brüssel, Yiddish: בריסל / Brisl, Hebrew: בריסל)

The first Jewish community of Brussels existed by the 1200s CE and produced culturally significant works such as an illuminated Torah manuscript completed in 1310. However, in the mid-1300s Jews were massacred after being blamed for the Black Plague. Another massacre in 1370 resulted in all Jews being expelled from the city. It was not until 1795 that Jews were allowed to live in Brussels without restrictions.

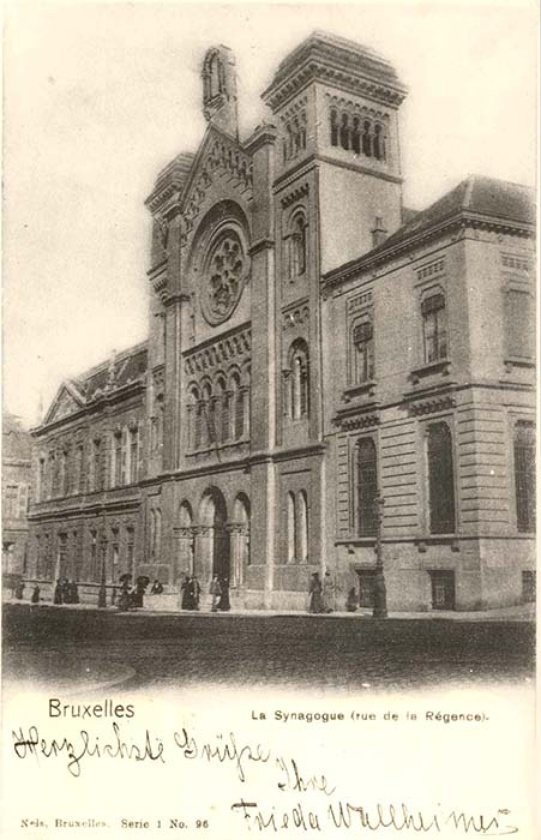

Belgium became an independent country in 1830 following centuries of Spanish, Austrian, French and finally Dutch rule. The new Constitution of 1831 granted freedom of religion to all citizens and by 1846 more than 500 Jews lived in Brussels. The city’s population was devastated by a cholera outbreak 20 years later. Notably, the Dieweg cemetery established to bury the victims of the disease included a section for Jewish burials. In 1878 the Great Synagogue of Brussels opened on the main thoroughfare of Rue de la Régence demonstrating government recognition of Jews as full citizens.

The Jewish population of Brussels continued to grow, especially as new immigrants from eastern Europe began to arrive around the 1880s. Leaders of the Jewish community organization (Consistoire) sought to foster a sense of Belgian citizenship. Others joined the Zionist movement that advocated for the creation of a separate Jewish state.

During World War I (1914-1918) Belgium was occupied by Germany and the country suffered violence and food shortages. Jewish immigrants from eastern Europe continued to arrive in Brussels after the war. The father of Survivor Ruth Deitch came from Belarus and worked for the Consistoire. Similarly, the parents of Pauline Rubin (née Cramarz) and Arthur Shapiro were born in Poland. Rubin remembered that although her parents spoke Polish and the Jewish language of Yiddish, she grew up speaking only French. Some families kept kosher and maintained Orthodox traditions, while others, like Shapiro’s family, “would go to the synagogue [only] for the big holidays.”

By 1933 the approximately 30,000 Jews of the city made up roughly 15 percent of Brussels’ total population. That year Hitler became Chancellor of Germany and Brussels saw another influx of Jewish immigrants, this time from Germany. Survivor Paula Proler recalled how she joined a Jewish youth organization to aid German refugees, saying, “We used to get money together and feed them.”

In May 1940 Germany invaded Belgium. The next year Jewish children were expelled from public schools and in 1942 Jews were forced to wear a Star of David on their clothing. Rubin remembered how her mother refused to wear the symbol and “tore it up.” Other acts of resistance included the publication of underground newspapers such as “La Libre Belgique” (The Free Belgium).

In September 1942, Nazis began to round up Jews and deport them to concentration camps. The Belgian Queen Mother Elizabeth intervened to protect Jews with Belgian citizenship helping many but leaving immigrants from eastern Europe especially vulnerable. Only four years old in 1942, Survivor Theo Meicler later recalled, “The first very clear memory that I have is when the Gestapo came into the house and arrested my father.” Meicler and several other survivors escaped the Nazi grasp by going into hiding, and the Committee for Jewish Defense succeeded in saving about 8,000 Jews across Belgium. Nonetheless, by the end of the German occupation in September 1944 more than 25,000 Jews from Belgium had been killed.

After the war, the Jewish community of Brussels was one of few to revive in Europe and in 2008 the Great Synagogue of Brussels was rededicated as the Great Synagogue of Europe. In 2016 the Jewish population of Brussels numbered about 20,000. However antisemitic prejudices have persisted into the 21st century and four people were killed during an attack on the Jewish Museum of Belgium in May 2014.

Bruxelles: Photographs & Artifacts

-

The Dieweg cemetery was founded in Brussels in 1866 following a citywide cholera outbreak. It included sections for both Catholic and Jewish burials. Credit: Wikimedia Commons / Moise Abramovitch / CC-BY-SA-3.0

The Dieweg cemetery was founded in Brussels in 1866 following a citywide cholera outbreak. It included sections for both Catholic and Jewish burials. Credit: Wikimedia Commons / Moise Abramovitch / CC-BY-SA-3.0 -

The Great Synagogue of Brussels opened in 1878 on the main thoroughfare of Rue de la Régence. Credit: Yad Vashem

The Great Synagogue of Brussels opened in 1878 on the main thoroughfare of Rue de la Régence. Credit: Yad Vashem -

Group portrait of students and teachers from the Hebrew school at the Synagogue rue Clinique Anderlecht in Brussels, Belgium, 12 July 1938. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Eva Tuchsznajder Lang

Group portrait of students and teachers from the Hebrew school at the Synagogue rue Clinique Anderlecht in Brussels, Belgium, 12 July 1938. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Eva Tuchsznajder Lang -

Group portrait of the staff of the Nos Petits Jewish kindergarten, ca. 1942-1944. The woman in the center is wearing a Star of David. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Olivia Mattis Noemi Mattis

Group portrait of the staff of the Nos Petits Jewish kindergarten, ca. 1942-1944. The woman in the center is wearing a Star of David. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Olivia Mattis Noemi Mattis -

A family in Brussels wearing the Jewish badge. Credit: Yad Vashem

A family in Brussels wearing the Jewish badge. Credit: Yad Vashem -

German soldiers surrendering in Brussels, September 1944. Credit: Yad Vashem

German soldiers surrendering in Brussels, September 1944. Credit: Yad Vashem -

The Great Synagogue of Brussels in June 2007. Credit: Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

The Great Synagogue of Brussels in June 2007. Credit: Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

Destroyed Communities Memorial Slope

Bruxelles: Survivors

We were a family, a nice family. We were seven kids, and life was pretty good.

I was woken up … by bombing all through the night.

The first very clear memory that I have is when the Gestapo came into the house and arrested my father.

[My husband] could have saved himself, but he didn’t want to leave me with the two children. So they took him.

I am sad about my lost childhood. I thank G-d that I was not taken in a camp. I thank G-d I was living. I thank G-d that my parents lived. But I’m angry that I lost my childhood.

We slept in trains. I remember we were really packed in those trains… sometimes we would walk on roads.