Berlin

Jews have lived in Berlin since the city was first settled in the late 1100s. However, their rights were often restricted. For example, a 1295 law prohibited wool merchants from supplying Jews with yarn. When the Black Death besieged Europe in the mid-1300s Jews’ houses were burned and they were either killed or forced to leave the city. Over the following centuries Jews continued to face restrictions on where they could live and were often required to pay extra taxes.

It was not until the Prussian Emancipation Edict of 1812 that Jews were recognized as citizens. The Jewish population of Berlin increased from about 3,000 in 1812 to more than 172,000 in 1925 and the city became known as a center of multiculturalism and tolerance.

In the early 1800s, the Jewish Reform movement began offering religious services in German rather than Hebrew. In contrast to more Orthodox traditions, men and women were seated together. Numerous cultural societies were founded to support the growing Jewish community including the Society for Jewish Culture and Learning founded in 1819. One of the Society’s members, the poet Heinrich Heine, wrote in 1823 that, “Where they burn books, they will also burn people.” Other Jewish organizations included the League of Jewish Women, as well as numerous religious, sport and other groups.

Men from Jewish families fought for Germany alongside their non-Jewish neighbors during World War I (1914-1918). Survivor Irma Frankel remembered that her father “went to war in 1914 and didn’t come back until 1920. He was a war prisoner in Siberia.” After the war, Germany became a representative democracy known as the Weimar Republic.

Throughout the period of the 1920s and 1930s, Berlin’s Jews made significant contributions to the thriving artistic, cultural and scientific life of the city. Albert Einstein, one of the most prominent Jewish scientists of Berlin, later emigrated to the United States.

Among survivors from Berlin, their parents’ professions ranged from furniture sales to tailoring to a linen supplier. Irma Frankel remembered growing up in “a mixed neighborhood, with both Jewish and non-Jewish businesses.” Most families spoke German at home, and were, in the words of Survivor Laure Wittner, “totally assimilated” into German life and culture.

Most Jewish children attended public school, their education often supplemented with religious instruction at a cheder (Jewish elementary school) or Hebrew school. In the 1920s Berlin had more synagogues than any other European city. Religious practices of survivors ranged from traditional Orthodox customs to more liberal Reform practices. Irma Frankel remembered, “We kept kosher and we belonged to a very nice, large synagogue… Passover was wonderful. All the relatives came.”

Although Berlin had a reputation for openness, not all residents were equally tolerant of their Jewish neighbors. In fact, the term “antisemitism” was coined by an anti-Jewish journalist in Berlin in the late 1870s. After World War I Jews were accused of deliberately sabotaging the war effort with a “stab in the back” and found themselves the victims of more frequent antisemitic attacks. Survivor Ernst Werner remembered being beaten up as a child where “I was the only ‘Jew boy’ in a school of 600 children.” Fellow Survivor Steve Landon remembered that some of his teachers “ridiculed Jews and attacked you personally if you didn’t do something right.”

The rise of Hitler in January 1933 would mean the destruction of a community that had thrived under decades of toleration. The Nuremberg laws passed in September 1935 deprived Jews of their citizenship and right to vote. Three years later, during the Kristallnacht pogrom of November 1938, Survivor Benjamin Waserman remembered how his father’s clothing business was looted. He recalled watching as Nazis “broke all the glass” from the front of local businesses, throwing the merchandise “out in the street.” Between 1939 and 1943 any Jews discovered living in Berlin were deported to the concentration camps. The city was officially declared “free of Jews” on June 16, 1943.

Berlin: Photographs & Artifacts

-

Pedestrians and shoppers walk past outdoor vendors in the Berlin Jewish quarter, 1929. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, College Park

Pedestrians and shoppers walk past outdoor vendors in the Berlin Jewish quarter, 1929. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, College Park -

A man, woman, and two children look out from the windows in this photo from the collection of Survivor Ernst Werner. Holocaust Museum Houston Permanent Collection: 1995.011.e

A man, woman, and two children look out from the windows in this photo from the collection of Survivor Ernst Werner. Holocaust Museum Houston Permanent Collection: 1995.011.e -

The dining hall at Beith Ahawah ("House of Love") Children's Home on Auguststrasse in Berlin. Beith Ahawah was paid for by the Jewish Council. With the economic problems of the early 1930s, many parents could not support their children and asked that the school care for them. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Ayelet Bargur

The dining hall at Beith Ahawah ("House of Love") Children's Home on Auguststrasse in Berlin. Beith Ahawah was paid for by the Jewish Council. With the economic problems of the early 1930s, many parents could not support their children and asked that the school care for them. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Ayelet Bargur -

The synagogue at the Baruch Auerbach Jewish orphanage in Berlin, 1931. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Stephan H. Lewy

The synagogue at the Baruch Auerbach Jewish orphanage in Berlin, 1931. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Stephan H. Lewy -

Germans pass by the broken shop window of a Jewish-owned business that was destroyed during Kristallnacht, November 10, 1938. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, College Park

Germans pass by the broken shop window of a Jewish-owned business that was destroyed during Kristallnacht, November 10, 1938. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, College Park -

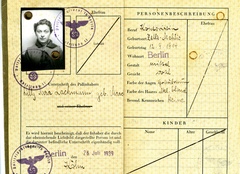

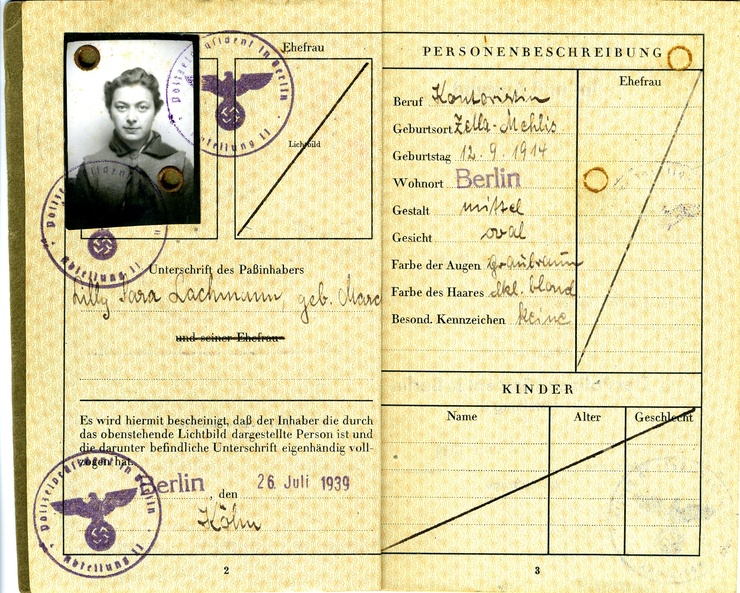

This 1939 passport for Lilly Lachman shows that she, like all Jews in Germany, was given the middle name Sara. It lists her occupation as "office clerk." Holocaust Museum Houston Permanent Collection: 2002.008.005

This 1939 passport for Lilly Lachman shows that she, like all Jews in Germany, was given the middle name Sara. It lists her occupation as "office clerk." Holocaust Museum Houston Permanent Collection: 2002.008.005 -

The synagogue on Fasanenstrasse that was ruined in Kristallnacht, April 16, 1941. Credit: Yad Vashem

The synagogue on Fasanenstrasse that was ruined in Kristallnacht, April 16, 1941. Credit: Yad Vashem -

The synagogue on Fasanenstrasse that was ruined in Kristallnacht, April 16, 1941. Credit: Yad Vashem

The synagogue on Fasanenstrasse that was ruined in Kristallnacht, April 16, 1941. Credit: Yad Vashem -

The synagogue on Prinzregentstrasse street which was ruined on Kristallnacht, 1958. Credit: Yad Vashem

The synagogue on Prinzregentstrasse street which was ruined on Kristallnacht, 1958. Credit: Yad Vashem

Destroyed Communities Memorial Slope

Berlin: Survivors

We kept kosher and we belonged to a very nice, large synagogue. It had a beautiful choir and wonderful rabbi. … Passover was wonderful. All the relatives came. We had as many as between 30 and 40 in our house.

I was in World War II and I was in the Korean War. The reason I was a second time in the Army, I wanted to thank the country for letting me in and my family in. I felt that I was obligated.

My bar mitzvah was scheduled on April 1, 1933 ... and the Nazis declared this as the first Jewish boycott day in Germany. ... I was bar mitzvahed, but there was after this no festivity because we were afraid. They were attacking and beating up Jews.

John Horst Schindler was born in Berlin, Germany on May 14, 1926.

This is my philosophy: If it weren’t for the people that helped us, we wouldn’t be here. That’s with the Germans, too. There are some people with a heart.

We didn’t have enough food, we didn’t have enough clothing, but there was always enough money to go to the opera. That was about the only thing we could afford. A ticket to the opera was only three rubles, and a loaf of bread on the black market was 300 rubles. So we spent a lot of time in the opera. And the sopranos and the tenors kind of silenced the growlings in our stomachs. – Anna Steinberger, recalling her courtship with Emil

“I remember we had a Jewish bakery down the street. On Kristallnacht they broke all the glass in the front and they just threw all the cakes out in the street. It was just total chaos. And the police…they just stood around, they just laughed. They had a grand old time.

I’m one of the few German Jews who does speak Yiddish because my father-in-law was from Tarnów, and he taught me Yiddish.

I remember at the frontier leaving Germany we had to get off the train and they searched us. And we had nothing. We could take nothing. We had just a little suitcase. We could take no money. At that point, they had taken everything and we went with nothing of our lives.