Lodz

Pronounced “Woodj” (Russian: Лодзь, German: Lodz, Yiddish: לאדזש / Lodzh, Hebrew: לודז')

The first known Jewish settlers of Łódź, a baker and a tailor, arrived in the Polish village in the late 1700s. Within the next decade, the region was annexed to the Prussian (German) Empire. The Jewish community grew and built its first synagogue in 1809, followed by the first Jewish cemetery in 1811. In 1815 the region became part of the Russian Empire and would be subject to Russian administration for the next hundred years.

Over the following decades Łódź became more and more industrialized, earning the nickname “Polish Manchester” for its many textile factories. Economic opportunities attracted immigrants from across Europe, adding to the diverse population of ethnic Poles, Germans and Jews. By the end of the 1800s, the Jewish population reached more than 98,000—nearly a third of the city’s total residents.

Within the Jewish community, some maintained traditional Orthodox beliefs while others followed Reform Judaism. Adherents of Reform Judaism were more likely to belong to the middle and upper classes. Jews owned about 60 percent of the textile shops and warehouses in the city. By contrast, many Jewish factory laborers lived in the impoverished suburb of Bałuty where they worked in sweatshops.

By the early 1900s the diverse Jewish population of Łódź enjoyed a thriving culture which included multiple libraries, theaters and two Yiddish-language newspapers. Many organizations promoted the use of the Yiddish and Hebrew languages, especially in support of the active Zionist movement that sought to establish an independent Jewish state.

Survivors Henri Cramarz and David Konstat were born in Łódź in the early 1900s, a time when the city still belonged to the Russian Empire. Konstat’s father served in World War I (1914-1918) as a soldier in the Russian army. In 1915, Łódź was occupied by German troops and many of its factories were plundered for equipment.

After the war, Łódź was incorporated into the new Polish Republic. Survivor Frank Gorme remembered growing up in “a fantastic city” where his family lived in a primarily Yiddish-speaking neighborhood. Other Jewish families, including the family of Survivor Helen Colin, lived in non-Jewish neighborhoods and spoke Polish at home.

Regardless of language, many survivors remembered the important role that religion played in their communities. Colin recalled that the shul where her family attended services was “very active” and “very close knit like … a family.” Boys in Łódź were often sent to private schools for Jewish religious instruction while most Jewish girls attended public schools. An exception, Survivor Esther Davidson attended a Beis Yaacov religious school for girls.

Although the Jews of Poland had known antisemitism for centuries, attacks against Jews increased after Adolf Hitler became the Chancellor of neighboring Germany in 1933. Survivor Bernard Gerszon remembered a pogrom in 1936 when members of the Polish antisemitic National Democracy (Endek) party “beat up Jews in the street in the middle of the day and broke windows, put houses to fire.”

Nazi forces occupied Łódź on September 8, 1939. Within a few months, the approximately 233,000 Jewish residents of the city were required to mark their clothing with a yellow Star of David. Survivor Walter Kase recalled, “You stopped being a person. You became a thing that the foreign power, the Nazi war machine, could do with anything they wanted.” By the end of the year a ghetto was created around the impoverished area of Bałuty, with multiple families crowded into one apartment.

Deportations to the Chełmno killing center began in January 1942. Those left behind faced starvation and disease. In August 1944 any surviving inhabitants were sent to Auschwitz. What was once the second-largest Jewish community in Poland had been annihilated. When Survivor Helen Colin returned to Poland after the war to look for the Jewish cemetery she found only a potato field.

Lodz: Photographs & Artifacts

-

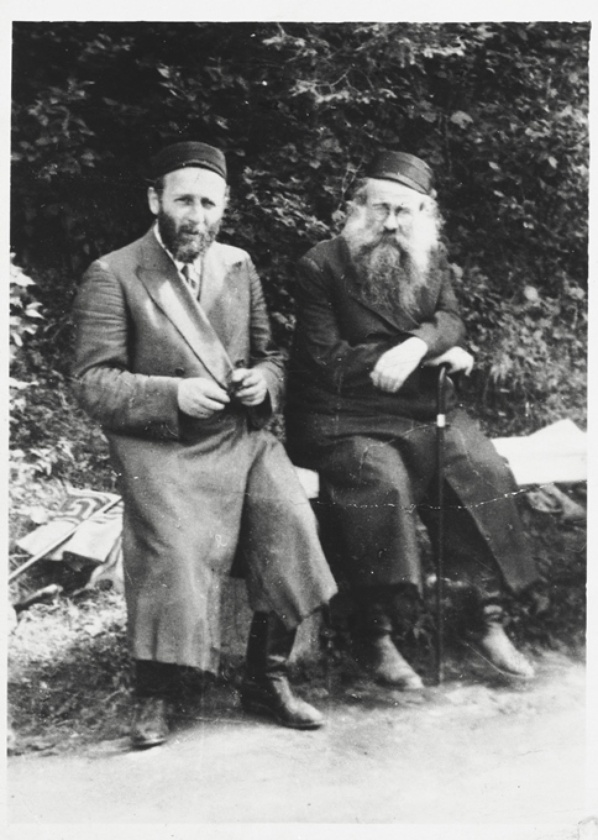

Two Hasidic Jewish men sit on a park bench in Łódź, ca. 1925-1939. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Marilka (Mairanz) Ben Naim, Ita (Mairanz) Mond and Tuvia Mairanz

Two Hasidic Jewish men sit on a park bench in Łódź, ca. 1925-1939. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Marilka (Mairanz) Ben Naim, Ita (Mairanz) Mond and Tuvia Mairanz -

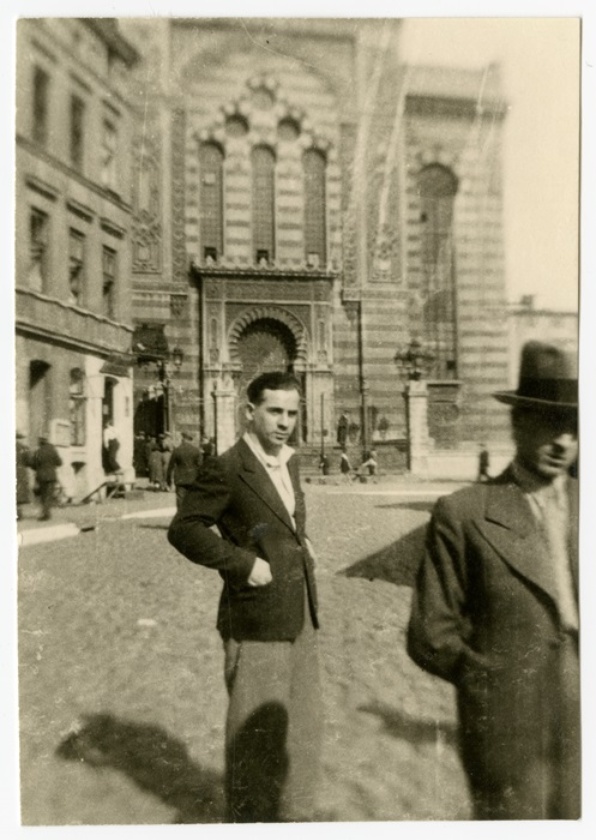

An unidentified man stands in front of the great synagogue in Łódź, ca. 1935-1939. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Moshe Zilbar

An unidentified man stands in front of the great synagogue in Łódź, ca. 1935-1939. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Moshe Zilbar -

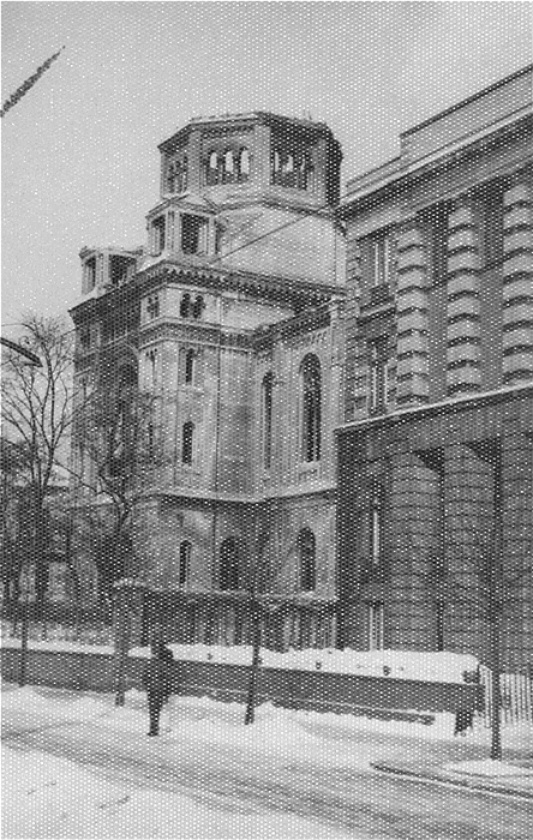

View of the destroyed reform synagogue on Kosciuszko Boulevard in Łódź, after November 14, 1939. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Frank Morgens (Mieczyslaw Morgenstern)

View of the destroyed reform synagogue on Kosciuszko Boulevard in Łódź, after November 14, 1939. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Frank Morgens (Mieczyslaw Morgenstern) -

Jewish men and women entering the Łódź ghetto, March 1940. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Raphael Aronson

Jewish men and women entering the Łódź ghetto, March 1940. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Raphael Aronson -

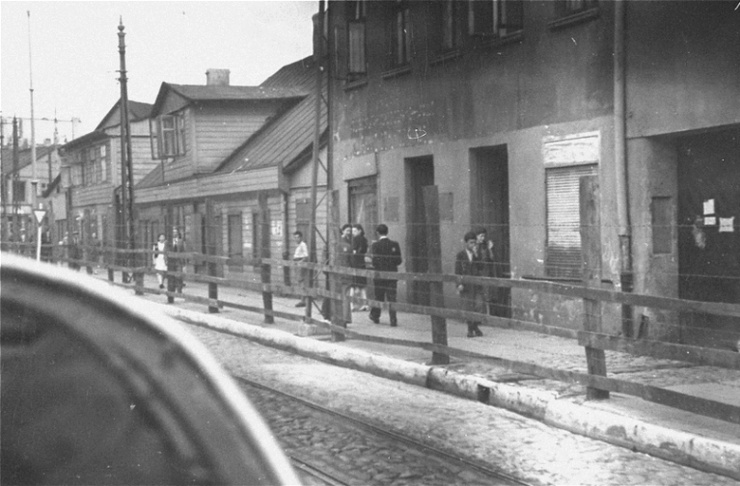

Łódź ghetto Jews behind the wooden and barbed wire fence that separated the Łódź ghetto from the rest of the city, ca. 1940-1941. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Frank Morgens (Mieczyslaw Morgenstern)

Łódź ghetto Jews behind the wooden and barbed wire fence that separated the Łódź ghetto from the rest of the city, ca. 1940-1941. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Frank Morgens (Mieczyslaw Morgenstern) -

Children working in a wood workshop in the Łódź ghetto, ca. 1941-1942. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Moshe Zilbar

Children working in a wood workshop in the Łódź ghetto, ca. 1941-1942. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Moshe Zilbar -

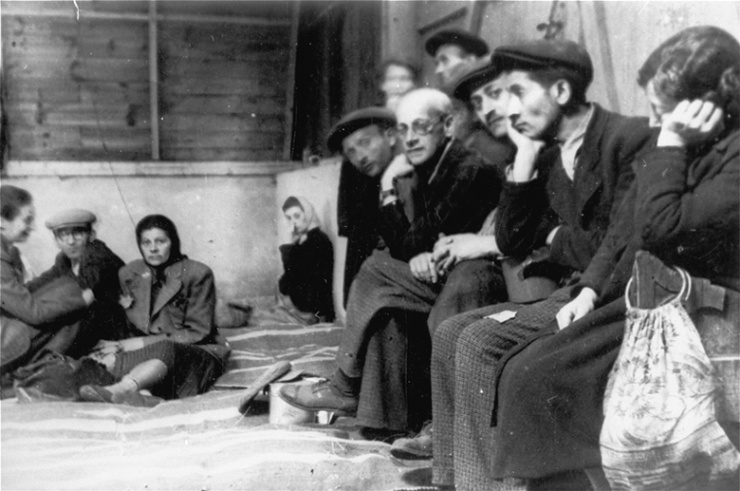

Jews who have been rounded-up for deportation in the Łódź ghetto are held at an assembly point on Krawiecka Street until trains are available to transport them out of the ghetto, ca. 1942. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Nachman Zonabend

Jews who have been rounded-up for deportation in the Łódź ghetto are held at an assembly point on Krawiecka Street until trains are available to transport them out of the ghetto, ca. 1942. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Nachman Zonabend

Destroyed Communities Memorial Slope

Lodz: Survivors

In the ghetto, the baby started crying and the mother, when we were all there, took the pillow, covered the baby’s face and—I will never forget it—she remained stiff with her arms because she knew she killed the child to save all of us.

We were a family, a nice family. We were seven kids, and life was pretty good.

I haven’t had any brothers and sisters since 1944, since I was sent to Auschwitz.

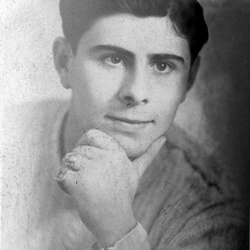

Rose Eisenstein was born Rose Obarzanek on January 1, 1923 in Łódź, Poland.

In the ghetto I buried my grandfather and my grandmother. I had to dig a grave for three days with one of those iron picks because the land was frozen. This was in 1941, January. They died literally from hunger, and that’s all.

Dr. Mengele was standing over there and the selection started, left, right, left. We didn’t know what this means. My whole family, my father and my sister and my two brothers were standing, and I went on the side to live with my two brothers. My father almost went through and Mengele grabbed him with a stick by his neck… I know that they will take him and they will kill him.

The ghetto was very, very bad. There was torture. There were people dying on the streets.

I never felt that being Jewish was going to change my life, that I was going to lose my family because of it. I did not grow up in a clannish environment. I grew up, really, in an environment kind of similar to where I live right now.

I had 72 interpreters working under my orders, Germans. All of them were members of the Nazi Party with big distinctions and all that, and I was the boss. … I was so scared. My aim was only to get out.

Rose Eisenstein was born Rose Obarzanek on January 1, 1923 in Łódź, Poland.

When it all started I was two and a half. When it finished I was eight and a half. … We grew up in our heads very, very quick. A kid of age four or five was an adult.