Krakow

Pronounce "KRAH-koov" (German: Krakau, Yiddish: קראָקע / Kroke, Hebrew: קרקוב, English: Cracow, Spanish: Cracovia)

The first Jewish merchants began to pass through Kraków as early as 1028 CE. By the 1300s this presence had developed into a full-fledged community. The Jewish street of Medieval Kraków grew to include two synagogues, a bathhouse, hospital and a Jewish cemetery outside the city walls. The Old Synagogue was completed in 1407 and today is the oldest medieval synagogue left standing in Poland.

Despite promises of protection from Polish kings, Jews continued to face persecution that periodically erupted into violent pogroms. In 1494 the Jews of Kraków were blamed for a citywide fire and forced to move south of the city walls to the neighboring area of Kazimierz (pronounced Kah-ZHEE-myezh). Eventually incorporated into the city, Kazimierz would serve as the center of Jewish life in Kraków for the next 400 years.

By the late 1700s the traditional Orthodox community of Kazimierz began to change as the Hasidic movement, with its focus on mysticism and prayer, gained popularity across Europe. Throughout the next century Jews were able to take advantage of economic opportunities provided by industrialization, especially after a railway line to Vienna was completed in 1844.

Although most Jews continued to speak Yiddish and follow traditional Orthodox practices, the Reform movement that advocated assimilation into the national culture also gained adherents. Survivor Martin Stoger recalled that his “extremely religious” grandfather observed the Sabbath by not answering the telephone on Saturdays, but “insisted that Polish be the language of the house, which was unusual in those times.”

A new Haskalah (Jewish Enlightenment) network of schools developed alongside the more traditional system of cheders (Jewish elementary schools) and yeshivas (schools to study Jewish religious texts). The first Reform temple in Kraków was completed in 1862 and in the late 1800s the newly founded Zionist movement began to attract followers who envisioned a national Jewish homeland.

By 1900 three parallel Jewish educational systems existed in Kraków: Hebrew language (Zionist), Yiddish language (Orthodox) and Polish language (assimilationist). Survivor Louise Joskowitz (née Stopnicka) and her brother Sol Stopnicki both attended private Hebrew and Jewish schools. Joskowitz recalled, “We had very good educational Jewish Schools in Kraków.”

In the 1920s and 1930s the institutions of the Jewish community included seven brotherhoods, such as the Chevra Kaddisha burial society, and 13 other institutions, including a number of reading rooms and libraries. Adding to these were a number of Jewish cinemas, sports clubs and dozens of Jewish newspapers.

By the 1930s the Jewish population of Kraków comprised about 25 percent of the city’s 220,000 inhabitants. Kazimierz encompassed a rich world of synagogues, shops and homes located throughout its winding and narrow streets. Religious life centered around the six synagogues and 66 prayer houses of the city.

However, Jews continued to contend with centuries-old antisemitism. In 1923 Jews made up 32 percent of all students at the city’s Jagiellonian University, but this number decreased to 12 percent in 1937 due to a quota that limited the number of Jewish students. Survivor Sol Stopnicki recalled, “Jews were afraid” explaining that students at universities “were fighting the Jewish students, they were throwing rocks.”

The city was occupied by German forces on September 6, 1939, and Kraków became the seat of the Nazi General Government in occupied Poland. Jewish organizations were banned, while Jewish homes, buildings and synagogues were desecrated and destroyed. Jews were sent to forced labor camps, and all Jewish inhabitants of the city were confined within the Kraków ghetto that was established in March 1941. The final liquidation of the ghetto took place on March 14, 1943, as any remaining inhabitants were transported to Auschwitz.

The tourists who now visit the synagogues of Kazimierz are able to glimpse only shadows of the centuries-old Jewish community of Kraków that was brutally extinguished during the Holocaust.

Krakow: Photographs & Artifacts

-

Photographer Roman Vishniac captured this view of the entrance to Kazimierz, the Jewish district of Kraków, ca. 1935-38. Holocaust Museum Houston Permanent Collection: 2015.001.007

Photographer Roman Vishniac captured this view of the entrance to Kazimierz, the Jewish district of Kraków, ca. 1935-38. Holocaust Museum Houston Permanent Collection: 2015.001.007 -

This photo by Roman Vishniac shows Isaac Street, Kazimierz, Krakow, ca. 1935-38. Holocaust Museum Houston Permanent Collection: 2015.001.012

This photo by Roman Vishniac shows Isaac Street, Kazimierz, Krakow, ca. 1935-38. Holocaust Museum Houston Permanent Collection: 2015.001.012 -

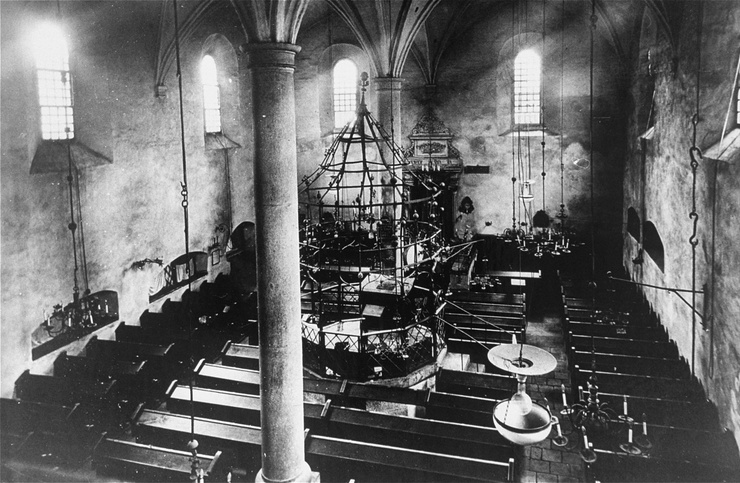

View of the Alte Schul [Old Synagogue] in the Kazimierz quarter of Kraków. Photo taken before 1939. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Archiwum Państwowe w Krakowie

View of the Alte Schul [Old Synagogue] in the Kazimierz quarter of Kraków. Photo taken before 1939. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Archiwum Państwowe w Krakowie -

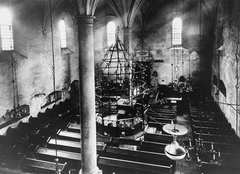

Interior of the Alte Schul [Old Synagogue], built in 1407 in the Kazimierz quarter of Krakow. Photo taken before 1939. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Archiwum Państwowe w Krakowie

Interior of the Alte Schul [Old Synagogue], built in 1407 in the Kazimierz quarter of Krakow. Photo taken before 1939. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Archiwum Państwowe w Krakowie -

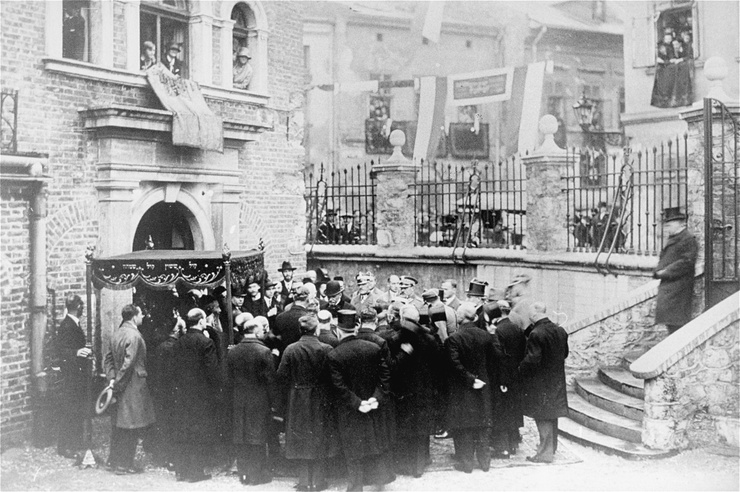

Leaders of the Jewish community greet General Józef Piłsudski in the courtyard of a synagogue in Kraków, September 30, 1927-October 1, 1927. As the leader of Poland between the two World Wars, Piłsudski supported Jewish rights. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Archiwum Państwowe w Krakowie

Leaders of the Jewish community greet General Józef Piłsudski in the courtyard of a synagogue in Kraków, September 30, 1927-October 1, 1927. As the leader of Poland between the two World Wars, Piłsudski supported Jewish rights. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Archiwum Państwowe w Krakowie -

Chief Rabbi of the Polish Army Boruch Steinberg poses with a group of Polish officers in a Kraków synagogue, 1935. Rabbi Steinberg was later killed in the 1940 Katyń massacre. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Simon Schochet

Chief Rabbi of the Polish Army Boruch Steinberg poses with a group of Polish officers in a Kraków synagogue, 1935. Rabbi Steinberg was later killed in the 1940 Katyń massacre. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Simon Schochet

Destroyed Communities Memorial Slope

Krakow: Survivors

I was a very happy-go-lucky child, active in all sports that one could imagine, climbed trees, fences.

In hiding there was a great deal of uncertainty on everyone’s mind because no one had any idea how long this was going to last. What would ever happen if our keeper below, something happened to him? We were fully at the mercy of one man.

From my window I could see the [Wawel] castle. ... Kraków was a beautiful town.

The hunger was terrible. People can’t even imagine how hunger can gnaw at you. How you can get hungry and all that you can do is think about hunger. That’s all you do is think day and night about a dry piece of bread.

When I was about two and a half years old, I remember playing outside of our house in Kraków and I heard bombs at a distance. I didn’t know what they were, large noises, running back to my parents and they figured out the war had come.

We kept kosher at home and observed Shabbat, Friday night dinner and Saturday afternoon dinner. We used to go to synagogue on Friday evening and Saturday, me and my father.