Breslau

Polish: Wrocław (Pronounced VROHTS-wahv)

The earliest Jewish community of Breslau dated back to the 1100s and included two synagogues as well as a Jewish cemetery. A Judenbischof (Bishop of the Jews) served the four roles of rabbi, cantor, kosher butcher and teacher. However, most of the community was massacred in 1349 when Jews were blamed for the Black Death.

Over the next few centuries, Jews’ rights were restricted and they were subject to discriminatory policies. For example, a 1577 law required all Jews to wear a yellow disc on their clothing. It was not until the 1700s that a more permanent Jewish community began to take root in Breslau. A new synagogue and cemetery were completed in 1761, one year after a new Jewish hospital opened to serve the community’s growing needs.

At the end of the 1700s, the Haskalah (Jewish Enlightenment) movement gained popularity. Followers of the Reform movement used German rather than Hebrew in their worship services, often leading to conflict with the more traditional Orthodox community.

In 1812 the Prussian Edict of Emancipation finally granted Jews equal rights as citizens. Societies for social and charitable work included the Israelite Study and Reading Club founded in 1842. The city’s Jewish Theological Seminary was founded in 1854 and became one of Europe’s premier Jewish seminaries.

While Orthodox Jews usually worshipped in the White Stork Synagogue built in 1829, Reform services were held in the grand New Synagogue that opened in 1872. The competing factions reached a historic compromise in 1856 by agreeing to two community rabbis that would be funded by a common organization.

The Jewish population grew exponentially, increasing from 3,255 in 1810 to 19,743 by the turn of the century. This time period also saw the rise of nationalist antisemitism. In 1892 a member of the Reichstag (German national parliament) gave a speech in Breslau on “Why Anti-Semitism Must Succeed.” However, the town council rejected proposals to bar Jewish teachers from public schools. Questions about the Jewish religion were even asked on the “Abitur” exam required for high school graduation.

From 1911 to 1918, the Jew Eduard Bernstein represented Breslau in the Reichstag. During World War I (1914-1918) Jews and Christians joined the military to fight for Germany. Survivor Simon Margoliner remembered how his father was drafted in 1916, leaving his family to forage for potatoes to feed themselves. In total, 450 Jews from Breslau died in battle during the conflict.

By the 1920s children and teenagers could choose from about 80 clubs, including the Griffins scouting group. Most families spoke German at home and Breslau was known for its high integration of Jewish citizens in community life. Explained Margoliner, “Most of the Jews were first Germans and then Jewish.”

Although the majority of Jewish children attended public schools, by 1932 about 15 percent of Jewish children were enrolled in the Orthodox school and about 30 percent of Jews attended Orthodox synagogues. Survivor Renate Berk recalled that her parents attended an Orthodox synagogue on high holidays though the family did not keep kosher at home.

Attacks on Jews began to rise as the Nazi party became increasingly influential. In 1920 a Jewish political leader was murdered in Breslau. A few years later more than 100 Jewish stores were looted during a 1923 demonstration in which many Jews were wounded and some killed. In 1932 Nazi students hurled tear-gas bombs into the university lectures of a Jewish professor. That year 43.5 percent of Breslau residents voted for the Nazi party. The following January Hitler became Chancellor of Germany.

The New Synagogue (built in 1872) was burned down during the Kristallnacht pogrom of November 1938. Margoliner remembered, “I was in[side] when they started to smash on the windows, the big windows.” He described how the Gestapo took him to the police station, then “they took us to the railroad to Buchenwald.”

The last remaining Jews of Breslau were transported to the Theresienstadt concentration camp in the summer of 1943. Only 160 members of the Jewish community of Breslau survived the Holocaust.

Breslau: Photographs & Artifacts

-

A woodcut of Breslau from the Nuremberg Chronicle published in 1493. Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain (PD-1996)

A woodcut of Breslau from the Nuremberg Chronicle published in 1493. Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain (PD-1996) -

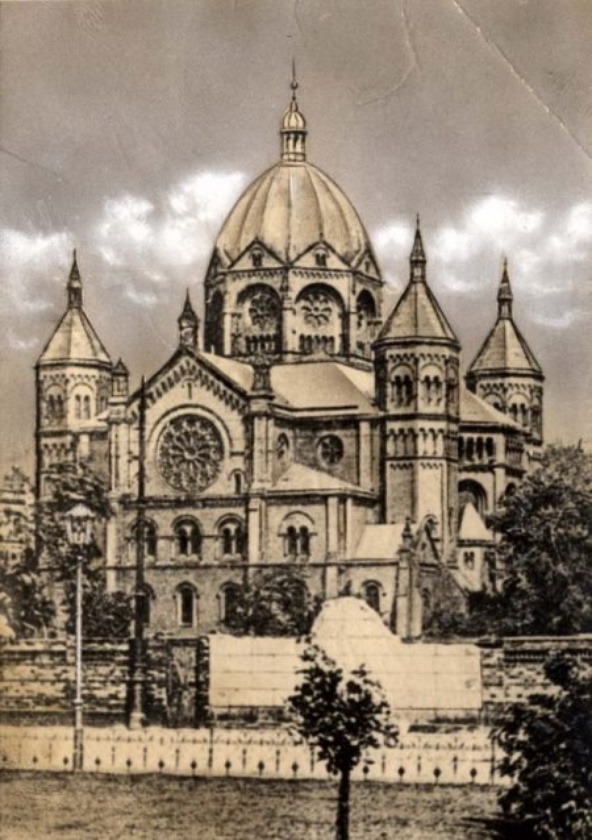

A synagogue in Breslau. Credit: Yad Vashem

A synagogue in Breslau. Credit: Yad Vashem -

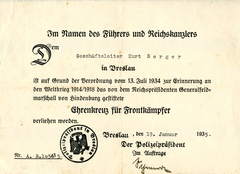

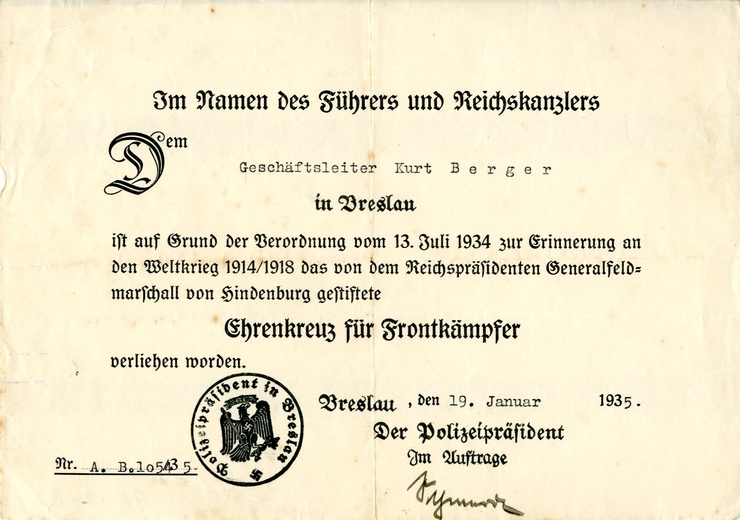

On January 19, 1935 Kurt Berger was awarded the Cross of Honor for his military service during World War I. Later that year he would be stripped of his German citizenship according to the Reich Citizenship Law of September 1935. Holocaust Museum Houston Permanent Collection: 1995.134.d

On January 19, 1935 Kurt Berger was awarded the Cross of Honor for his military service during World War I. Later that year he would be stripped of his German citizenship according to the Reich Citizenship Law of September 1935. Holocaust Museum Houston Permanent Collection: 1995.134.d -

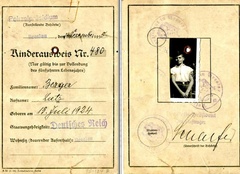

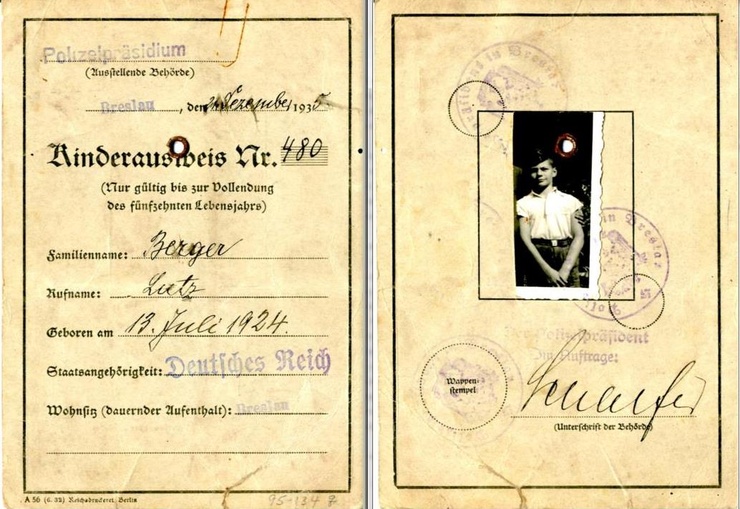

This identification card for Lutz Berger was issued in Breslau in December 1935. Holocaust Museum Houston Permanent Collection: 1995.134.q

This identification card for Lutz Berger was issued in Breslau in December 1935. Holocaust Museum Houston Permanent Collection: 1995.134.q -

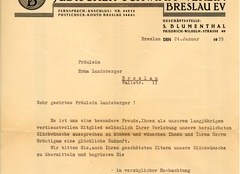

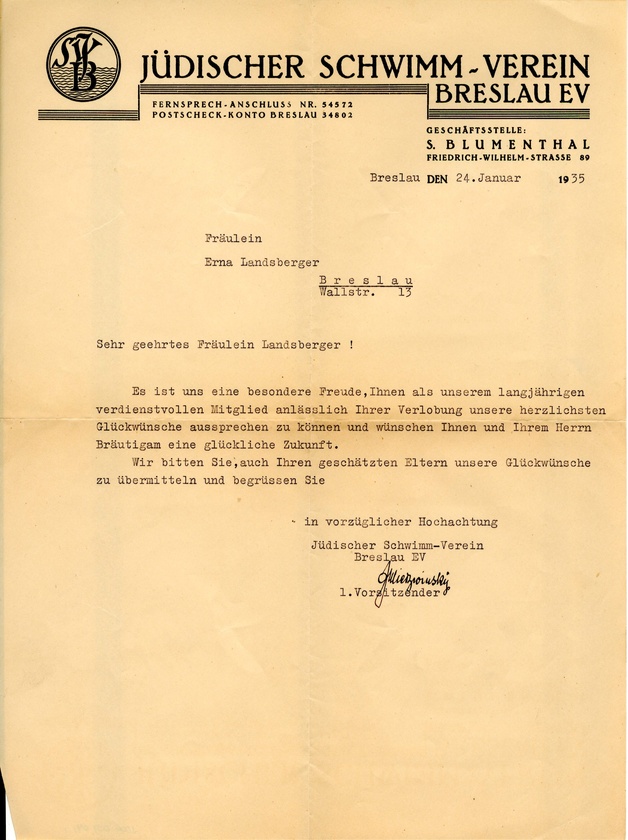

The Jewish swim team of Breslau congratulates longtime team member Erna Landsberger on her engagement. Holocaust Museum Houston Permanent Collection: 2006.039.041.001

The Jewish swim team of Breslau congratulates longtime team member Erna Landsberger on her engagement. Holocaust Museum Houston Permanent Collection: 2006.039.041.001 -

A Jewish cemetery, 1985. The destruction is still evident decades after the Holocaust. Credit: Yad Vashem

A Jewish cemetery, 1985. The destruction is still evident decades after the Holocaust. Credit: Yad Vashem

Destroyed Communities Memorial Slope

Breslau: Survivors

When we emigrated my parents took clothes for my brother and me in several sizes, so they wouldn’t have to buy once they got to South Africa. This was bad, because as far as we were concerned, the clothes didn’t look like South African clothes and that didn’t make my brother and me very happy. . . . We didn’t want to be different.

The first thing that happened to us is that we lost our names. No longer were we individuals. Now we became numbers. Each of us received a number, and we were to remember this number, and eventually we sewed it on our jackets. Our hair was shaved off, and we were told that we are no longer human beings. We were now subhumans, and as such we will be treated. So it will be up to us to fall in line and accept the situation or, if we object, the end will be death, and they meant it.

The Jews in Germany … were equal to every other guy. … Most of the Jews were first Germans and then Jewish. …Most of them made a good living, because they were equal, equal.