Hamburg

Pronounced “HAHM-burg” (Low German: Hamborg, French: Hambourg)

The first known Jewish residents of Hamburg arrived around 1575, a time when the northern European port city officially belonged to Denmark. This early Jewish community maintained the Sephardi culture of Jews who had been expelled from Spain and Portugal. Most worked in jobs that supported the city’s trade, for example as shipbuilders, goldsmiths or importers of goods from Spanish and Portuguese colonies.

By 1611 Hamburg counted three synagogues and the Jewish population reached about 560 within the next decade. Around the same time, an influx of Ashkenazi, or central European Jews, began to settle in the city. Members of both Jewish communities faced temporary bans as well as restrictions on Jewish trade and worship. A violent anti-Jewish protest erupted around 1730.

In 1768 Hamburg became part of Germany and an 1808 decree again limited Jewish life. Jews enjoyed a brief period of equal rights when French troops under Napoleon took over the city from 1811 to 1814. The Jewish Temple that opened in Hamburg in 1818 was one of the first synagogues to incorporate Reform elements into its worship, for example using German rather than Hebrew in parts of the service.

Jewish residents of Hamburg were terrorized by the antisemitic “Hep! Hep!” riots that spread throughout Germany in 1819. More anti-Jewish riots followed in 1830 and 1835. The Jewish community was further devastated when large sections of the city burned down during a three-day fire in May 1842. However, after the fire Jews were no longer confined to specific neighborhoods and had freedom to live throughout the city.

Jews were finally granted citizenship in 1850. Nine years later, nine Jewish men were elected to the city’s 84-member parliament. By the late 1800s, most Jewish families were highly assimilated into German culture and Jewish men fought for Germany alongside their countrymen during World War I (1914-1918). One of these soldiers, the father of Survivor Ilse Goldberg, returned home with a concussion and temporary memory loss. Despite the sacrifices of Jewish men, the city experienced a spike in antisemitic violence during the war and the Sephardi Jewish cemetery was desecrated in 1916.

The Jewish community of Hamburg faced an existential threat with Hitler’s accession to power in January 1933. Nazis orchestrated a boycott of Jewish businesses in April and soon all Jews were barred from working in government positions. Ilse Goldberg’s father lost his job as a master electrician. From 1933 to 1937, thousands of Jewish residents fled the city. Survivor Ludwig Brand was only five months old when his family moved to Kraków, Poland in the summer of 1933.

Conditions for those who remained in Hamburg continued to grow worse. On the night of November 9, 1938, Jewish homes, businesses and synagogues were burned and destroyed during Kristallnacht. More than 900 Jewish men were sent to the Fuhlsbüttel concentration camp. Then, between 1941 and 1943 an estimated 5,000 Jews were deported from Hamburg to concentration camps and Jewish ghettos in eastern Europe. The Jewish community was officially liquidated in 1943. Most of the roughly 1,800 who survived in the city were married to non-Jews, including the father of Survivor Ilse Goldberg.

In July 1943, allied British and U.S. forces conducted strategic air raids against the city of Hamburg. Goldberg remembered bombs falling overhead, saying, “Everybody was screaming.” Large sections of the city were destroyed before German troops surrendered to British forces on May 3, 1945.

Of a prewar population of about 17,000, by the spring of 1945 fewer than 650 Jews lived in Hamburg. Estimates of the number of Jewish residents from the city killed in the Holocaust range from about 7,800 to nearly 9,000.

Hamburg: Photographs & Artifacts

-

This Portuguese (Sephardi) synagogue in the Altona district was dedicated in 1771. The building was razed in 1940. Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

This Portuguese (Sephardi) synagogue in the Altona district was dedicated in 1771. The building was razed in 1940. Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain -

Interior of the synagogue in den Kohlhoefen, Hamburg, 1920. Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

Interior of the synagogue in den Kohlhoefen, Hamburg, 1920. Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain -

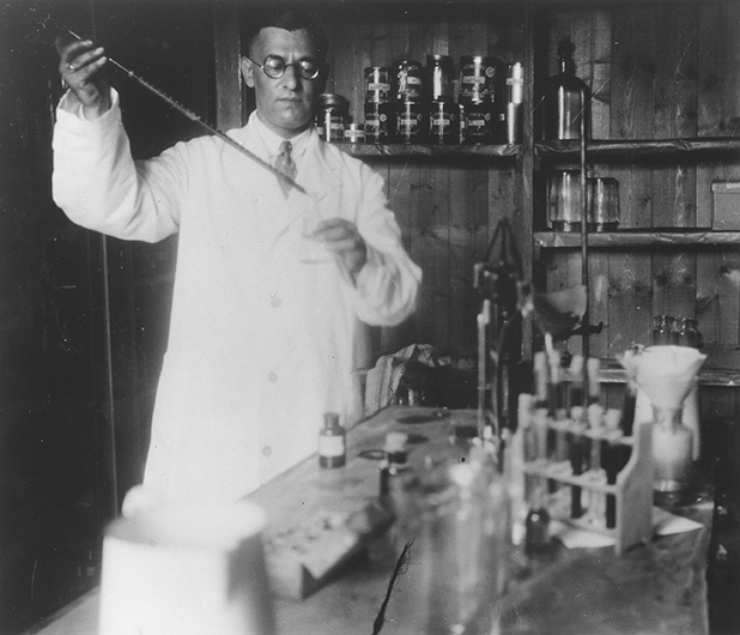

A chemist at work in his laboratory in Hamburg, Germany, ca. 1930-1938. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Peter Gelbart

A chemist at work in his laboratory in Hamburg, Germany, ca. 1930-1938. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Peter Gelbart -

A parade of the Nazi party in Hamburg,

A parade of the Nazi party in Hamburg, -

Passengers boarding the St. Louis ship, 13 May 1939. Most were Jewish refugees sailing for the United States. The boat reached Cuba but the US government refused the passengers entry to the US and the ship returned to Europe. Credit: Yad Vashem

Passengers boarding the St. Louis ship, 13 May 1939. Most were Jewish refugees sailing for the United States. The boat reached Cuba but the US government refused the passengers entry to the US and the ship returned to Europe. Credit: Yad Vashem -

Ruins of the Great Synagogue in Hamburg. Credit: Yad Vashem

Ruins of the Great Synagogue in Hamburg. Credit: Yad Vashem -

A Jewish cemetery in Hamburg in a state of neglect, postwar. Credit: Yad Vashem

A Jewish cemetery in Hamburg in a state of neglect, postwar. Credit: Yad Vashem

Destroyed Communities Memorial Slope

Hamburg: Survivors

In hiding there was a great deal of uncertainty on everyone’s mind because no one had any idea how long this was going to last. What would ever happen if our keeper below, something happened to him? We were fully at the mercy of one man.

In 1941, when friends came to the house with the [Star of] David, they had a notice to go to Theresienstadt. … They had a small child about 18 months old—a girl, curly haired beautiful baby. We never heard from them again.