Praha

Pronounced “Prah-hah” (English: Prague, German: Prag, Hebrew: פראג, Yiddish: פּראַג / Prog)

Jewish traveler Ibrāhīm ibn Ya‘qūb first noted Jews living in the historic city of Prague in the year 970 CE. A Jewish quarter established in the 1200s included the Alt-Neu (Old-New) Synagogue completed in 1270. However, Jews were not always welcomed. For nearly two hundred years after the First Crusade was declared in 1095, Jews were murdered and forced to convert to Catholicism. Some 3,000 Jews were killed in 1389 and over the next centuries Jews were periodically banned from the city.

In 1526, the mixed Czech, German and Jewish populations of Prague came under the rule of the Hapsburg (Austrian) monarchy. The Jewish population doubled in the two decades from 1522 to 1541, and made up roughly two percent of the city’s 60,000 total inhabitants. From the late 1500s to early 1600s the Jewish community experienced a “Golden Age” of cultural, religious and scientific thought. According to legend, the famed Rabbi Yehuda Loew (d. 1609) created the Prague golem (clay giant) to protect the Jewish quarter and its residents.

The Jewish population of Prague continued to grow throughout the 1700s despite anti-Jewish policies, for example laws limiting the number of births in Jewish families. In 1852 the Jewish quarter was opened and renamed Josefstadt (Josefov in Czech), but full equality under the law was not reached until 1867.

By the late 1800s many Jewish families in Prague had begun to assimilate into German culture and adopt the German language. Others favored Czech acculturation. A third group joined the Zionist movement that emerged in the 1890s to advocate for the creation of an independent Jewish state.

After World War I (1914-1918) the Austro-Hungarian Empire dissolved and Prague became the capital of the new state of Czechoslovakia. Jewish cultural life in Prague included a number of Yiddish-language publications. The city was also home to German-Jewish author Franz Kafka.

Survivors Hana Ginzbarg and Tomáš Klima grew up in Prague in the 1920s and 1930s. They both remembered that Jewish families were highly integrated into Czech and German society. Intermarriage was common and Klima himself was born to a Jewish mother and Catholic father. Ginzbarg recalled that her father was “very active” in politics and in 1929 and 1931 some Jewish representatives were elected to the national parliament.

After Hitler came to power in 1933 Klima recalled “uneasy feelings” among the Jewish community of Prague. Some Jewish residents prepared to leave, including an uncle of Ginzbarg’s. An attorney, he “took a course in confectionery, baking cakes” to learn an alternate profession.

Germany invaded Czechoslovakia on March 15, 1939. Hana Ginzbarg remembered seeing German soldiers and their horses occupying the second floor of her school building. Nazi officials added more and more restrictions on Prague’s Jewish residents. Tomáš Klima recalled that his mother was forced to wear a yellow Star of David. She and her family were crammed into a ghetto where three families shared one apartment.

Jewish aid organizations attempted to alleviate the increasing suffering of the community by establishing orphanages, hospitals and a soup kitchen. Many Jews struggled to find ways to leave the city. Hana Ginzbarg and her brother were two of the children saved by British stockbroker Nicholas Winton, who arranged train journeys for more than 600 children to London.

Nazi transports from the Prague ghetto to Theresienstadt and other concentration camps began in October 1941. More than 46,000 people were deported over the next three and a half years, including the mother of Tomáš Klima. Although many of the Jewish artifacts and buildings in Prague were saved, the once-thriving Jewish community was destroyed.

Praha: Photographs & Artifacts

-

The Alt-Neu (Old-New) Synagogue in Prague was built in the 1200s. This photo from 1945 shows the building riddled with bullet holes. Credit: Yad Vashem

The Alt-Neu (Old-New) Synagogue in Prague was built in the 1200s. This photo from 1945 shows the building riddled with bullet holes. Credit: Yad Vashem -

The old Jewish cemetery in Prague was founded in the 1400s. This photo shows the cemetery as it looked in 1989. Credit: Yad Vashem

The old Jewish cemetery in Prague was founded in the 1400s. This photo shows the cemetery as it looked in 1989. Credit: Yad Vashem -

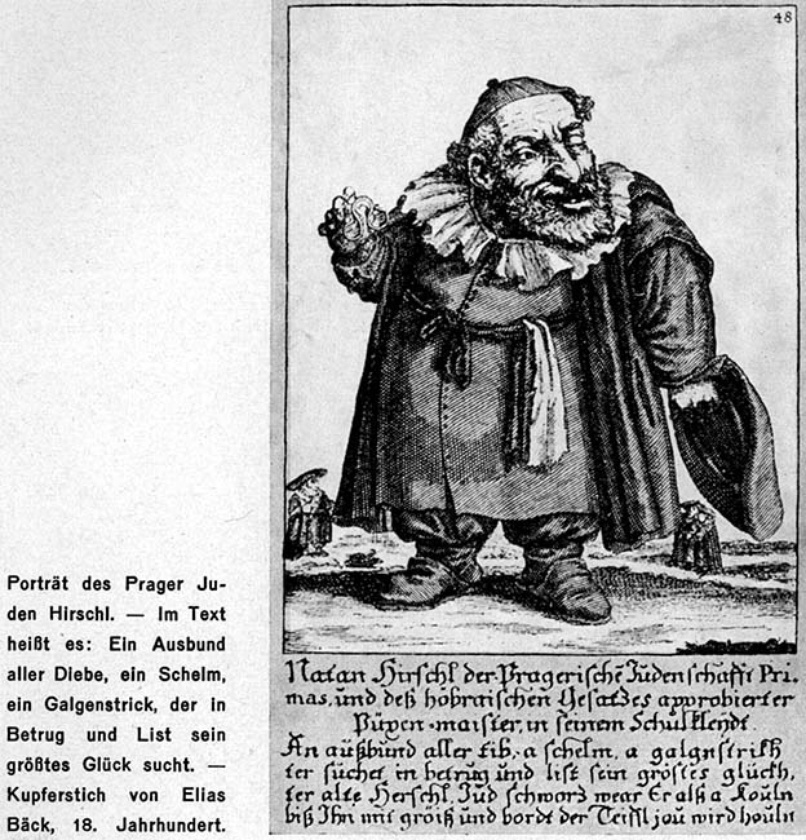

An antisemitic caricature entitled "Natan Hirschl the Prague Jew" from the 1700s. The image was used as propaganda after the Nazis came to power. Credit: Yad Vashem

An antisemitic caricature entitled "Natan Hirschl the Prague Jew" from the 1700s. The image was used as propaganda after the Nazis came to power. Credit: Yad Vashem -

Two Jewish soldiers in the Czech army, ca. 1935. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Amira Kohn-Trattner

Two Jewish soldiers in the Czech army, ca. 1935. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Amira Kohn-Trattner -

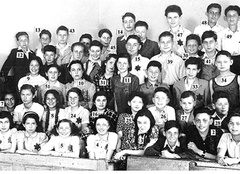

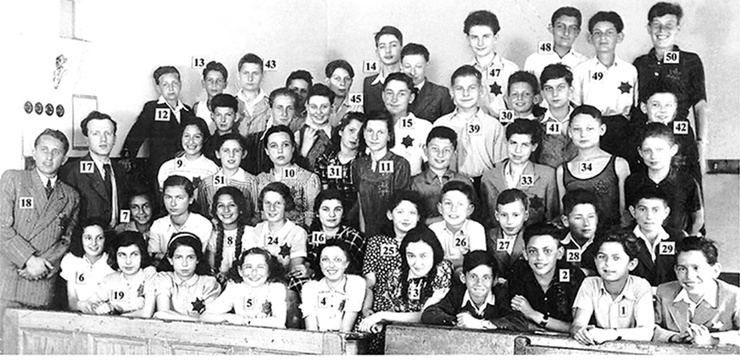

A school class in Prague, 3 May 1942. Only nine of the children in the photo are known to have survived the Holocaust. Credit: Yad Vashem

A school class in Prague, 3 May 1942. Only nine of the children in the photo are known to have survived the Holocaust. Credit: Yad Vashem -

Jewish forced laborers building a road in Prague, 1944. Credit: Yad Vashem

Jewish forced laborers building a road in Prague, 1944. Credit: Yad Vashem -

This Stolperstein, or "stumbling block" memorial, is located on Široká street in Prague, October 2010. Credit: Wikimedia Commons / Hans Weingartz / CC-BY-SA 3.0

This Stolperstein, or "stumbling block" memorial, is located on Široká street in Prague, October 2010. Credit: Wikimedia Commons / Hans Weingartz / CC-BY-SA 3.0

Destroyed Communities Memorial Slope

Praha: Survivors

My mother went to the railroad station, took us there. My brother was 11, I was 13. We cried—we didn’t want to go.

I was not even aware of my mother being Jewish. People didn’t care about it, at least in the society I was living in.