Bucuresti

Pronounced “Boo-koo-RESH-chee” (Romanian: București, German/Hungarian: Bukarest, Bulgarian: Букурѐщ / Bukurest, Ukrainian: Бухаре́ст / Bucharest, Serbo-Croatian: Bukurešt, Hebrew: בוקרשט / Bevqershet, Yiddish: בוקארעשט)

Jews lived in the city of Bucharest since at least the 1500s, a time when the region belonged to the Ottoman (Turkish) Empire. In 1593, the Jews of the city were massacred during a rebellion against the Turks.

Two centuries later, in 1801 more than 125 Jewish residents of Bucharest were killed during a series of antisemitic riots. Nonetheless, as a major economic center the city continued to attract a number of Jewish and non-Jewish immigrants. The Jewish community grew from about 200 families in 1800 to more than 40,000 individuals by the end of the century.

By 1832 Bucharest counted one Sephardi (Spanish) synagogue and 10 Ashkenazi (central European) places of worship. An extensive network of Jewish schools ranged from elementary education through advanced scriptural study. Although severely damaged in anti-Jewish riot in 1866, the new Choral Temple was completed in 1867. The Temple held services in Romanian, while more traditional Orthodox congregations worshipped in Hebrew.

Romania gained independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1878, but strong feelings of national identity often excluded Jews and contributed to rising antisemitism. In 1897 Jewish homes and businesses were looted. The weekly newspaper “Curierul israelit” (Israelite Courier) was founded in 1906 to expose antisemitism and report on the Zionist movement that advocated for the creation of an independent Jewish state.

Jews were among those who fought for Romania during World War I (1914-1918), despite the fact that Jews’ full rights as citizens were not recognized until the Constitution of 1923. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s the Jewish residents of Bucharest—both Sephardi and Ashkenazi—continued to enjoy a thriving culture that included 36 registered synagogues, a number of Jewish schools and a library with more than 7,000 volumes. While most families spoke Romanian at home, Survivor Zoly Zamir also knew German and Survivor Rosine Chappell recalled that the “aristocracy” of the country spoke French.

Unfortunately, the 1920s and 1930s also saw a resurgence of anti-Jewish discrimination. Beginning in 1922, quotas were imposed to limit the number of Jewish students at universities in Romania. The fascist Iron Guard party was founded in 1927 and Survivor Rosine Chappell remembered people shouting insults at her as she walked down the street. In 1937, Zoly Zamir and all other Jewish students were expelled from school.

Romania formally joined the Axis Alliance with Nazi Germany in November 1940. Zamir’s brother, Survivor David Singer, remembered “They started putting stamps on the ID” so that Jews “couldn’t go and shop. You couldn’t do the things that everybody else did.” Zamir recalled that “my late mother had a little hand embroidery shop, and they took away her license so that she could not continue to earn a living.” The Iron Guard “put a sign on every Jewish store warning people not to shop with us,” Chappell said.

During an antisemitic pogrom in January 1941, the haberdashery (sewing supply store) owned by Chappell’s father was looted and destroyed while a storeowner down the street was “killed, beaten to death.” The Great Temple of the Sephardi community was destroyed and hundreds of Jewish residents were tortured and killed. Both Singer and Zamir described the horror of later seeing the bodies of murdered Jews hung in the city’s slaughterhouse.

Singer was one of the tens of thousands of Jews in Bucharest deported to a labor camp where he struggled to survive, digging ditches and living in lice-filled barracks. Although Singer, his brother Zamir and Rosine Chappell were among those lucky to survive, the centuries-old Jewish community of Bucharest was destroyed.

Bucuresti: Photographs & Artifacts

-

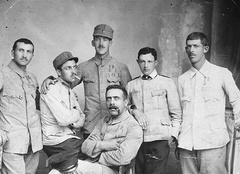

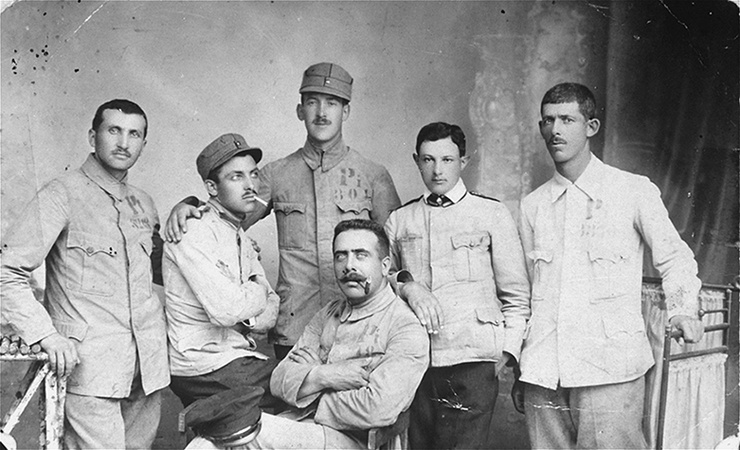

Group portrait of Jewish soldiers in the Romanian army during World War I, 15 July 1917. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Ion & Jeanine Gutman Butnaru

Group portrait of Jewish soldiers in the Romanian army during World War I, 15 July 1917. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Ion & Jeanine Gutman Butnaru -

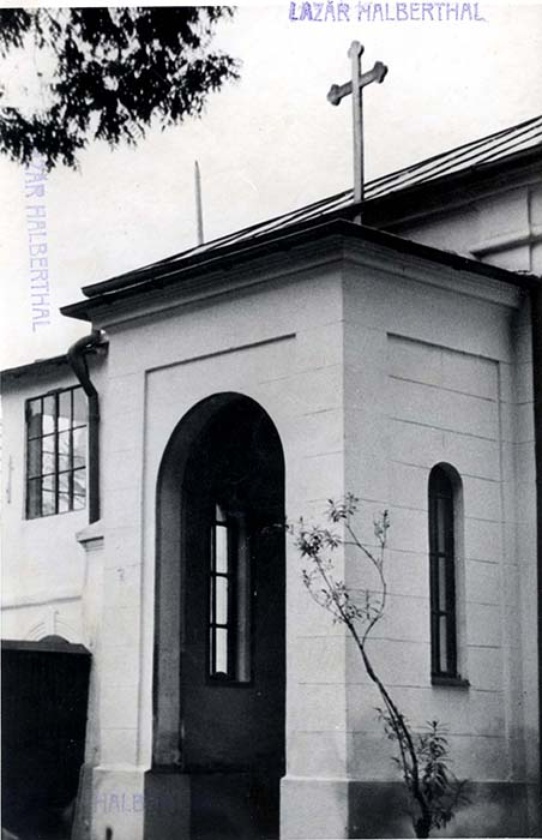

A building in Bucharest that used to be a synagogue. Credit: Yad Vashem

A building in Bucharest that used to be a synagogue. Credit: Yad Vashem -

Three Jewish women stroll down a commercial street in Bucharest, 24 August 1942. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Ion & Jeanine Gutman Butnaru

Three Jewish women stroll down a commercial street in Bucharest, 24 August 1942. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Ion & Jeanine Gutman Butnaru -

German soldiers entering Bucharest, 1941. Credit: Wikimedia / Bundesarchiv, N 1603 Bild-001 / Horst Grund / CC-BY-SA 3.0

German soldiers entering Bucharest, 1941. Credit: Wikimedia / Bundesarchiv, N 1603 Bild-001 / Horst Grund / CC-BY-SA 3.0 -

The Great Sephardi (Spanish) Synagogue in Bucharest that was destroyed in the pogrom of 22 January 1941. Credit: Yad Vashem

The Great Sephardi (Spanish) Synagogue in Bucharest that was destroyed in the pogrom of 22 January 1941. Credit: Yad Vashem -

A Jewish store in Bucharest destroyed during a pogrom, 23 January 1941. Credit: Yad Vashem

A Jewish store in Bucharest destroyed during a pogrom, 23 January 1941. Credit: Yad Vashem -

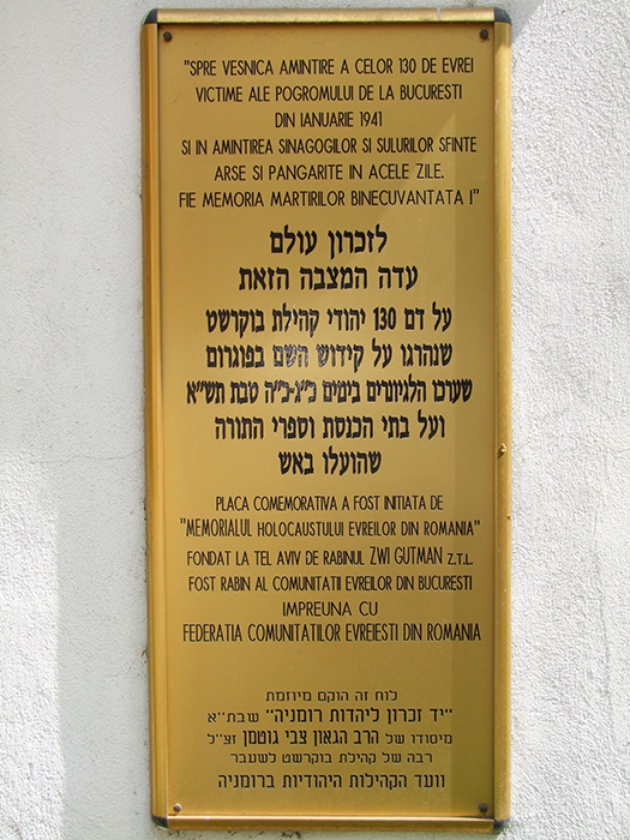

A memorial plaque at a synagogue in Bucharest commemorating the pogrom of January 1941. Credit: Yad Vashem

A memorial plaque at a synagogue in Bucharest commemorating the pogrom of January 1941. Credit: Yad Vashem

Destroyed Communities Memorial Slope

Bucuresti: Survivors

The [U.S.] State Department put an awful lot of impediments in anything that we tried to do. … To this day I have a lot of angry feelings about the fact that it was made so difficult for us to come here, and it was made impossible for some of our friends there. Some of them were imprisoned in camps back in Europe and ended up dying in the Holocaust.

In the camp I worked in the kitchen. I used to peel potatoes and I used to steal a little bit of a peeled potato and I put it in my mouth and chewed it so that a Nazi wouldn’t see me. … Of course I had no pockets. I used to steal a little bit of the peel from the potato and put it in my shoe so that I had in the evening something to eat.

I remember the first Saturday that I took a walk with my mother in Tel Aviv in 1948. The stores were all closed and she asked me, ‘Zolyke, is all of this Jewish?’ I said, ‘Yes.’ She was very, very impressed with that, that the stores were Jewish, the police were Jewish. Everybody was Jewish.