Frankfurt

Full name: Frankfurt am Main (French: Francfort-sur-le-Main)

Jewish traders conducted business in Frankfurt as early as the 1000s CE, however antisemitic massacres in 1241 and 1349 halted the growth of the community. Over the next centuries Jews faced a number of discriminatory policies ranging from higher taxes to a law requiring them to wear a yellow badge. In 1462 Jewish residents were confined to a Judengasse (Jews Alley) where the gates were locked at night as well as on Sundays and Christian holidays.

Despite these restrictions, by the mid-1600s the Jewish community of Frankfurt developed as a center of Hebrew printing and Jewish learning. About a hundred years later the Haskalah, or Jewish Enlightenment, encouraged secular education in addition to religious study. Also in the late 1700s, the Rothschild (Red Shield) family rose to prominence in the world of international finance and would remain influential in the Jewish community for centuries.

Still, the Judengasse in Frankfurt was not abolished until 1811. The Jewish community began to grow more steadily, from about 3,300 inhabitants in 1817 to approximately 8,200 in 1867. For 23 years (1867-1890) Jewish delegates represented the city in the national parliament.

Within the Jewish community, the Reform movement flourished as many Jewish families assimilated into national German culture. Some rabbis began to conduct services in German rather than Hebrew, however others protested the change. In 1882 a group of more traditional Orthodox believers inaugurated a new synagogue located in the former Judengasse. Like their leader Hungarian Rabbi Márkus Horovitz, many of these Orthodox followers were immigrants from eastern Europe.

Thousands of Jews from Frankfurt joined the German military during World War I (1914-1918). The fathers of survivors Anita Rothschild and Marcella Newman both returned home wounded from the conflict and were among those whose families considered themselves German first and Jewish second. Survivor Walter Sommers remarked that his parents “would fly the German flag whenever there was an occasion.”

Lingering prejudices remained within the Jewish community as immigrants continued to arrive from eastern Europe. Survivor Max Bamberger later remarked that some “had an attitude against eastern [European] Jews,” while Sommers remembered his mother saying “they are not really part of our crowd.” Many Reform families, like Sommers’, attended synagogue only “on high holidays, and maybe one more time” throughout the year. Still, he and other survivors received about one hour a week of Jewish religious instruction in the public schools they attended.

Few survivors reported any direct experiences of antisemitism in Frankfurt before Hitler was appointed chancellor in January 1933. Although Sommers remembered that he and classmates had previously “celebrated birthdays together,” after the Nazis came to power Jewish students were “socially isolated and cut off.” Rothschild recalled how “no one would sit with me” on the way to school. Other children even threw rocks at her as she walked to Hebrew lessons.

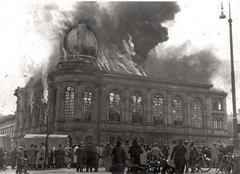

The Horovitz synagogue was one of several that was burned down and destroyed during the Kristallnacht pogrom of November 1938. Jewish homes and businesses were looted and more than 2,000 Jewish men were sent to concentration camps, including the fathers of Max Bamberger, Marcella Newman and Walter Sommers.

Many Jewish families fled Germany. The Jewish population of Frankfurt fell from about 29,385 in 1925 to 14,100 in May 1939. In September 1941, any Jews who were not able to leave the city were forced to wear a yellow Star of David. Ultimately they were deported to the killing centers. At the end of World War II only about 600 Jews remained in Frankfurt.

In 1950 the Westend Synagogue was renovated and rededicated. About 7,000 Jews lived in Frankfurt in 2003.

Frankfurt: Photographs & Artifacts

-

Rabbi Meyer and one of his students outside the synagogue in Frankfurt-am-Main, ca. 1935-1938. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Jacob G. Wiener

Rabbi Meyer and one of his students outside the synagogue in Frankfurt-am-Main, ca. 1935-1938. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Jacob G. Wiener -

Jewish students in a classroom at the Philanthropin school in Frankfurt, ca. 1937-1938. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Lore Gotthelf Jacobs

Jewish students in a classroom at the Philanthropin school in Frankfurt, ca. 1937-1938. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Lore Gotthelf Jacobs -

The Horovitz synagogue on Börneplatz in flames during the Kristallnacht pogrom, 9 November 1938. Credit: Yad Vashem

The Horovitz synagogue on Börneplatz in flames during the Kristallnacht pogrom, 9 November 1938. Credit: Yad Vashem -

Exterior of a ruined synagogue in Frankfurt. Credit: Yad Vashem

Exterior of a ruined synagogue in Frankfurt. Credit: Yad Vashem -

Ruins of a synagogue in Frankfurt. Credit: Yad Vashem

Ruins of a synagogue in Frankfurt. Credit: Yad Vashem -

View of the desecrated Jewish cemetery in Frankfurt-am-Main, ca. 1946-1948. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Herbert Friedman

View of the desecrated Jewish cemetery in Frankfurt-am-Main, ca. 1946-1948. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Herbert Friedman -

A memorial panel at the location of the Horovitz synagogue on Börneplatz which was destroyed on Kristallnacht. Credit: Yad Vashem

A memorial panel at the location of the Horovitz synagogue on Börneplatz which was destroyed on Kristallnacht. Credit: Yad Vashem

Destroyed Communities Memorial Slope

Frankfurt: Survivors

As a German Jew, I was active in … the Jewish Boy Scouts. I started in 1924 … I’ve been in Boy Scouts ever since.

Kristallnacht … was a real, real scary thing. It was at night and they came storming through our door … They came and arrested my father and put him in Dachau.

I shall never forget hearing Hitler speak on the radio, this rasping, hysterical voice, and it put the chills on me.

We would fly the German flag whenever there was an occasion. During the Weimar Republic days we would fly the black, gold and red flag. Then, of course, after 1933 we got a new flag.