Dusseldorf

Pronounced “Dooh-sehl-dorf” (old Dutch: Dusseldorp)

A small Jewish cemetery existed in Düsseldorf as early as 1418. However, over the next two hundred years Jews faced a number of bans from the city. It was not until the 1670s that Jewish families were able to settle more permanently. Some 24 Jewish families lived in Düsseldorf when the first synagogue was built in 1792.

The Jewish community of Düsseldorf continued to grow throughout the 1800s, adding a Jewish school as well as a number of new prayer houses and cemeteries. A Jewish man served on the city council from 1846 to 1848 and both Jewish and Christian residents actively participated in the revolutions of 1848 to 1849 against the Prussian (German) monarchy.

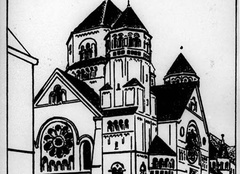

By 1900 the roughly 2,600 Jews of Düsseldorf made up about 1.2 percent of the city’s total population of approximately 214,000. The new Great Synagogue was built in 1904. Some controversy arose within the Jewish community when the congregation began to follow Reform practices, for example conducting parts of the service in German rather than Hebrew. More traditional Orthodox worshippers, often immigrants from eastern Europe, protested the change and started a new prayer room.

During World War I (1914-1918), a number of men in the Jewish community of Düsseldorf fought for Germany, including the fathers of survivors Ruth Brown and Gloria Lachman. Brown remembered how her family had lived in Germany “generations back” and “loved the country.”

Lachman recalled that her great-grandfather had started a synagogue in Düsseldorf and that her Orthodox family strictly observed kosher dietary laws. She remembered attending “the big synagogue on the Kasernenstraße,” describing it as “one of the most beautiful edifices you could ever imagine.” She added that “women sat upstairs and … the two other parts were for the men.”

As a young child Lachman recalled that she “never felt any antisemitism” from her classmates. In fact, she described a society more divided by class than religion, saying, “If you were an upper middle-class girl…you didn’t hang around with the other children that came from perhaps a more blue-collar background.”

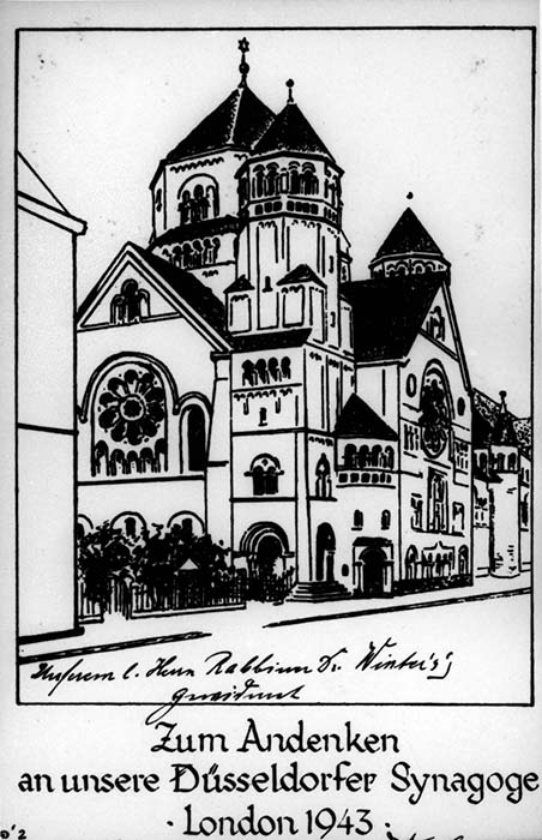

Nonetheless, antisemitic influences gained strength throughout the 1920s and 1930s. A Düsseldorf synagogue was desecrated in 1928 and Ruth Brown remembered that during recess “some of the non-Jewish children would come over and push the Jewish children down.” Walter Loeb recalled that he was often excluded from activities at his high school and was “unable to get into university” due to laws that restricted the number of Jewish students.

In April 1933, only a few months after Hitler was appointed Chancellor, Nazis organized a boycott of Jewish stores. Lachman recalled that in her father’s store, “our plate glass windows, five of them, were smashed.” Her father was arrested and she witnessed Nazis at the police department “standing with all kinds of whips, torture equipment.” Some of the prisoners were then sent to the Dachau concentration camp. In 1935 Jewish children were required to attend separate schools.

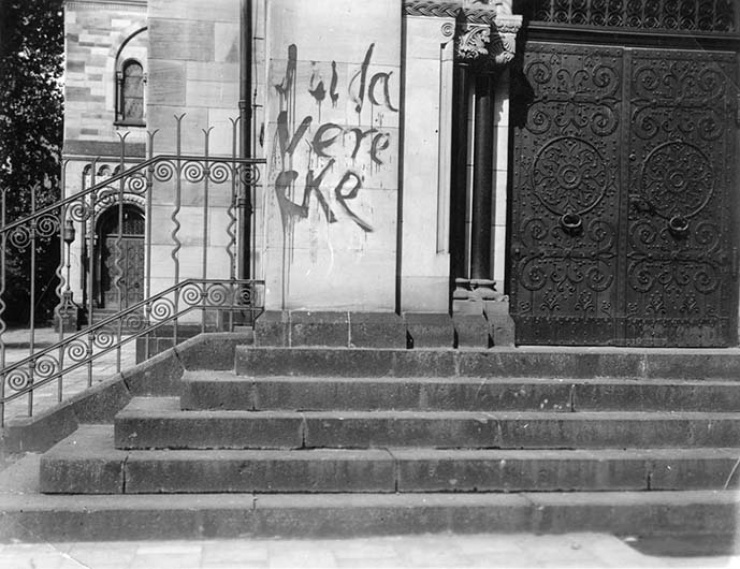

Then, on the night of November 9, 1938, Jewish homes, businesses and places of worship were looted and vandalized during the pogrom of Kristallnacht. Walter Loeb witnessed as Nazis forced Jews to throw scriptural scrolls and other sacred objects out the window of the Kasernenstraße synagogue before “using hammers and saws … to destroy the interior.” The synagogue was then set on fire while the fire department ensured the surrounding buildings were protected.

Mass deportations of the city’s Jewish residents to concentration camps began in 1941, with the final transport to Theresienstadt occurring in February 1945. More than 2,000 Jews from Düsseldorf were killed in the Holocaust.

Dusseldorf: Photographs & Artifacts

-

A drawing of the Great Synagogue. The caption reads: "In memory of our Düsseldorf synagogue, London 1943" Credit: Yad Vashem

A drawing of the Great Synagogue. The caption reads: "In memory of our Düsseldorf synagogue, London 1943" Credit: Yad Vashem -

A swastika and antisemitic inscription on a wall of the synagogue. Credit: Yad Vashem

A swastika and antisemitic inscription on a wall of the synagogue. Credit: Yad Vashem -

Nazi graffiti on an exterior wall of the synagogue. Credit: Yad Vashem

Nazi graffiti on an exterior wall of the synagogue. Credit: Yad Vashem -

Stolpersteine, or "stumbling blocks," can be found on sidewalks throughout Düsseldorf as memorials to the Jews who once lived in the city. This photo was taken in April 2016. Credit: Wikimedia Commons / Harald Malte Schwarz / Public Domain

Stolpersteine, or "stumbling blocks," can be found on sidewalks throughout Düsseldorf as memorials to the Jews who once lived in the city. This photo was taken in April 2016. Credit: Wikimedia Commons / Harald Malte Schwarz / Public Domain

Destroyed Communities Memorial Slope

Dusseldorf: Survivors

My father couldn’t speak any English when he came to America. He’d been a businessman all his life, but he was a wonderful person, he never complained, he was so grateful and so happy that he was in this country that never, not once, did I hear him complain about fate or how bad things were or how good things could have been if he had been able to stay over there. He was just happy to have a job and be in this country.

My mother nearly had a nervous breakdown right after World War II when the Red Cross sent out messages of all the people that were killed. Every day there was another letter. Her sisters are dead, her brother was dead, her brother-in-law was dead. On my father’s side, every single relative had been killed. Every single cousin, every single young person in this family is dead.

Having lost so much of our heritage in Europe, we project ourselves into the future through new generations. We are most fortunate in so many ways.

When Hitler came into power and the Hitler youth marched through the streets, I was very jealous that I wasn’t allowed to walk with them. Because in the early days it was a great fun thing. You didn’t realize the danger.