Wurzberg

Pronounced "VOORTS-berg"

The first known Jewish residents of Würzburg arrived as refugees fleeing persecution from the First Crusade in 1096 CE. Less than a century later about 20 Jews were murdered during the Second Crusade in 1147. The land used to bury the victims became the Jewish cemetery of the town and by 1170 this fledgling community had established its first synagogue.

Periodic outbursts of violence against the Jewish community persisted over the following centuries. For example, in 1298 approximately 900 Jews were murdered after the community was accused of desecrating the communion bread used in Christian worship. In the 1500s all Jews were banned from the city and had to wear yellow circular badges in order to enter and conduct trade.

Jews did not return as residents of Würzburg until the early 1800s when the city was annexed to the Kingdom of Bavaria. However, Jews continued to face antisemitic persecution and discrimination. The widespread “Hep! Hep!” riots of 1819 began in Würzburg and soon swept across Germany. Jews were murdered and their stores destroyed as rioters shouted slogans encouraging Jews to “drop dead.”

The Jewish community of Würzburg endured nonetheless and by the mid-1800s had established a synagogue, a Jewish teachers training school and a Chevra Kaddisha burial society. The late 1800s and early 1900s saw the addition of numerous charities such as an old age home and daycare for poor Jewish children. In 1900 the Jewish population reached about 2,500 people.

Like their neighbors, the Jewish citizens of Würzburg fought for Germany during World War I (1914-1918). These included the father and uncle of Survivors Otto Schlamme and Ruth Schnitzer (née Schlamme). The siblings recalled that they were raised as German citizens of the Jewish faith and were well integrated into German society. In the 1920s a Jew served as the mayor of Würzburg and a second synagogue was built for recently-arrived Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe.

The survivors’ grandfather was a well-respected doctor in the city who helped establish a new Jewish hospital that opened in 1930. Schnitzer remembered going with him as “he made his rounds by horse and buggy.” As children Schlamme and Schnitzer attended the local public Catholic school, where Schnitzer remembered being excused for Jewish religious instruction three times a week. Schlamme recalled “no animosity” from the other students.

However, antisemitic violence began to escalate after Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933. The Jews of Würzburg faced boycotts, riots and increasingly violent attacks. Schlamme remembered his father, a recipient of the Iron Cross medal, saying, “Don’t worry about that. The good German people cannot possibly put up with these Nazi hoodlums very long.” Despite these reassurances, the situation only worsened and the Schlamme family decided to leave Germany. The last members of the family departed for the United States on November 8, 1938. The next night Jewish homes, businesses and the two synagogues of the city were plundered and ruined during the nationwide pogrom of Kristallnacht.

In 1941 all German Jews were forced to wear yellow Stars of David on the outside of their clothing. The next year any remaining Jewish residents of Würzburg were forced out of their homes and crowded into the buildings of the Jewish cemetery. Soon afterward deportations to concentration camps began. Schlamme and Schnitzer’s beloved grandfather was deported to Theresienstadt in September 1942, where he died the next February. The final liquidation of the Jewish community occurred on September 22, 1943. Of a prewar population of more than 2,000, only 22 Jewish residents remained in the city.

Wurzberg: Photographs & Artifacts

-

The inside of the Great Synagogue in Würzburg, before the war. Credit: Yad Vashem

The inside of the Great Synagogue in Würzburg, before the war. Credit: Yad Vashem -

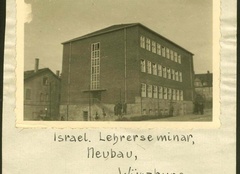

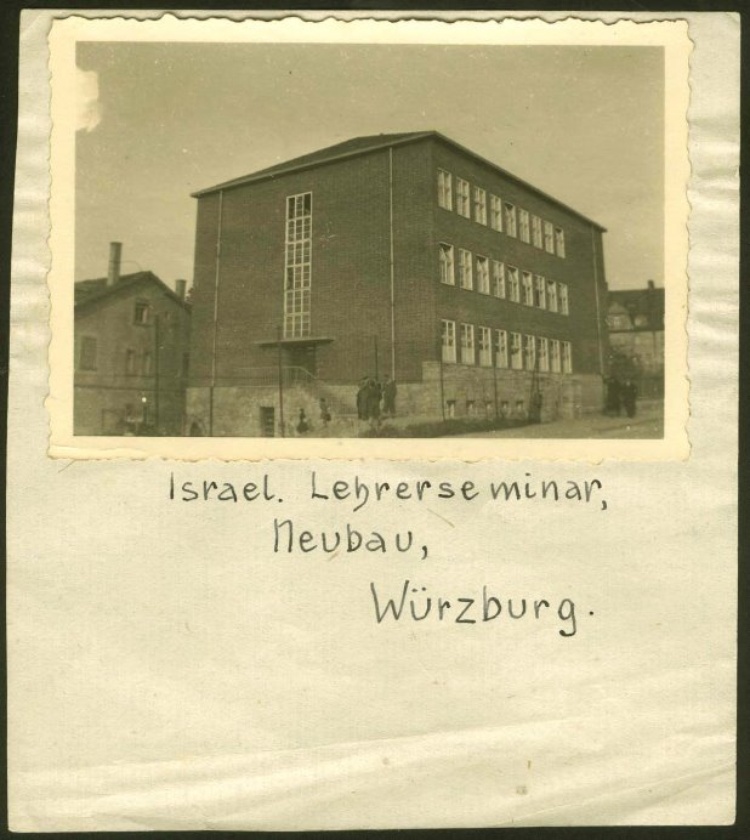

Jewish Teachers Training Seminary, before the war. Credit: Yad Vashem

Jewish Teachers Training Seminary, before the war. Credit: Yad Vashem -

The interior of a synagogue in the Jewish Teachers Training Seminary, before the war. Credit: Yad Vashem

The interior of a synagogue in the Jewish Teachers Training Seminary, before the war. Credit: Yad Vashem -

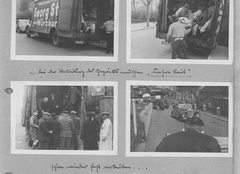

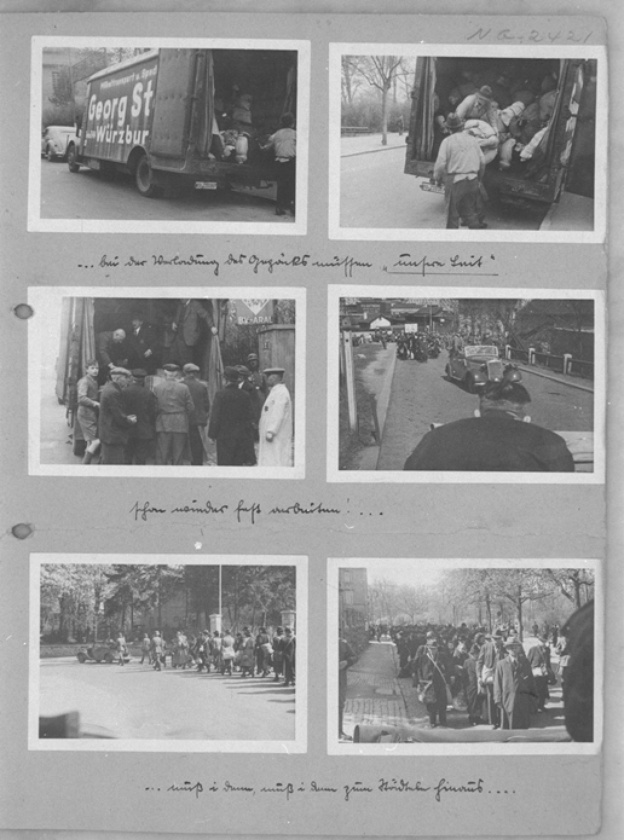

One page of a photo album depicting the deportation of the Jews from Wurzburg, 1942. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, College Park

One page of a photo album depicting the deportation of the Jews from Wurzburg, 1942. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, College Park -

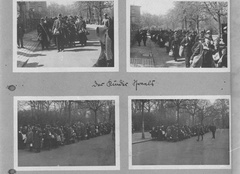

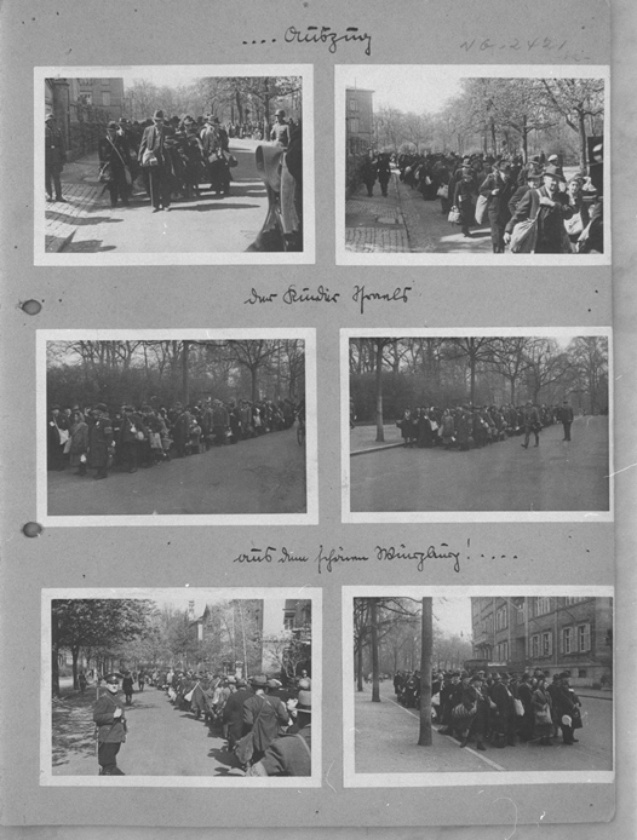

Another page of a photo album depicting the deportation of the Jews from Wurzburg, 1942. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, College Park

Another page of a photo album depicting the deportation of the Jews from Wurzburg, 1942. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, College Park

Destroyed Communities Memorial Slope

Wurzberg: Survivors

My mother was a concert violinist and her life revolved around music. There always was music in our home.

My grandfather chose to remain in Germany. He always did say, ‘Things will get better and I’m staying. Whenever you want to leave, I’m staying.’ And my grandmother on the other side also chose to remain in Germany. And they both perished.