Radom

RAH-dohm (Yiddish: ראדום / Rodem, Hebrew: ראדום, Russian: Радом / Radom)

The first Jews settled in Radom in the mid-1500s, but in 1633 were prohibited from residing within town limits. By 1798 about 90 Jewish citizens lived on the outskirts of the town with frequent travel within the city walls to conduct trade. That same year Radom was incorporated into the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Under the new rulers Jews were once again allowed to live in the city, but were confined to a designated Jewish quarter. Jewish business owners encountered frequent prejudice from members of the majority Roman Catholic population who feared economic competition.

The Jewish community of Radom built its first synagogue in the early 1800s around the same time that the first Jewish cemetery was consecrated in 1831. Ten years later all bans against Jewish economic activity were finally lifted. During this time many Jews worked as merchants, food producers and shopkeepers. Jews were also pioneers of the growing textile industry.

By 1897 the Jewish population in Radom counted more than 11,000 people (roughly 37 percent of the total population). In the early 1900s the thriving Jewish community could choose from more than 20 Yiddish-language newspapers and magazines, including “The Free Word” and “Radom Weekly.”

World War I (1914-1918) devastated the local economy as machinery and natural resources were depleted for the war effort. Russian soldiers murdered three Jews as the troops retreated and plundered the city.

After the war the Austro-Hungarian Empire dissolved and Radom was incorporated into the newly independent country of Poland. The city became an important center of industry as home to a gasworks and a telephone factory. In the 1920s Jews made significant contributions to the local economy as the owners of about 90 percent of small craftworks. Survivor Morris Goldberg remembered that his family “had a leather factory.” Similarly, Survivor Allen Wayne’s father worked as an administrator of a building supply company.

Jewish citizens played active roles in the Radom community. Survivor Anna Steinberger remembered that her father served on many civic committees saying, “he was considered one of the upright citizens in our city.” Steinberger’s father worked with other members of the Jewish community “helping the poor … feeding the children and trying to provide them with clothes or perhaps money to go to school.”

However, the rise of antisemitism across Europe in the 1920s and 1930s meant that the Jews of Radom experienced escalating harassment, especially as the local branch of the antisemitic National Democracy party gained popularity. Wayne recalled how other boys “were always throwing stones” at him as he walked to school. Many Jewish families no longer felt welcome in Radom. From 1932 to 1939 about 10,000 Jews emigrated to Palestine and other countries around the world.

Nazi Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939. An estimated 1,000 to 2,000 Jewish citizens fled to the Soviet Union on horse-drawn wagons including the family of Survivor Anna Steinberger. Any Jews who remained saw their rights quickly curtailed. In August 1940 Jewish men and women began to be deported to forced labor camps. All the surviving Jews of Radom were forced into one of two Jewish ghettos established in April 1941.

Between February to August 1942 the ghettos were liquidated. Some Jews were sent to forced labor camps while the majority were put on trains headed for the death camps at Auschwitz and Treblinka. The last labor camp was evacuated on July 26, 1944 when about 2,500 laborers were forced to march about 50 miles to a nearby town before they were sent to Auschwitz.

Radom was liberated by Soviet forces on January 16, 1945. Seven Jews remained in Radom in 1965, and by 2013 no Jews lived in the city.

Radom: Photographs & Artifacts

-

The home of the chief Rabbi and the synagogue in Radom. Credit: Yad Vashem

The home of the chief Rabbi and the synagogue in Radom. Credit: Yad Vashem -

A group of Jewish friends wearing armbands poses on and around a hay wagon near Radom shortly after the German invasion of Poland. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Marilyn Ackerman

A group of Jewish friends wearing armbands poses on and around a hay wagon near Radom shortly after the German invasion of Poland. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Marilyn Ackerman -

These stamps from October 1940 commemorated one year of Nazi rule in Radom. Courtesy of Anna Steinberger

These stamps from October 1940 commemorated one year of Nazi rule in Radom. Courtesy of Anna Steinberger -

View of the main square of the ghetto in Radom. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Archiwum Dokumentacji Mechanicznej

View of the main square of the ghetto in Radom. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Archiwum Dokumentacji Mechanicznej -

A burnt synagogue in Radom. Credit: Yad Vashem

A burnt synagogue in Radom. Credit: Yad Vashem -

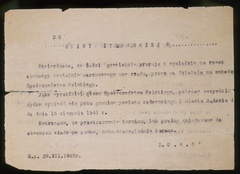

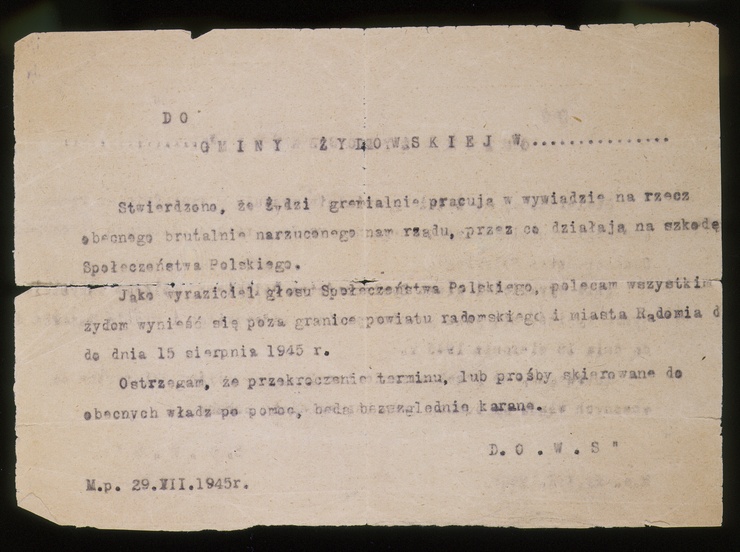

This document, dated July 29, 1945, was sent to Jews living in Radom after the war. It reads in part: 'It has been established that Jews are working for the current government that has been brutally imposed upon us and is detrimental to Polish society. I recommend that all Jews remove themselves beyond the borders of the city and district of Radom by August 15, 1945. I am warning, remaining beyond that date, or asking the present government for assistance will be punishable.' Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Manya Friedman

This document, dated July 29, 1945, was sent to Jews living in Radom after the war. It reads in part: 'It has been established that Jews are working for the current government that has been brutally imposed upon us and is detrimental to Polish society. I recommend that all Jews remove themselves beyond the borders of the city and district of Radom by August 15, 1945. I am warning, remaining beyond that date, or asking the present government for assistance will be punishable.' Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Manya Friedman -

A monument in Israel to Radom Jews who perished in the Holocaust. Credit: Yad Vashem

A monument in Israel to Radom Jews who perished in the Holocaust. Credit: Yad Vashem

Destroyed Communities Memorial Slope

Radom: Survivors

You live like a human being and all of a sudden they kill you…take everything away from you, everything.

We didn’t have enough food, we didn’t have enough clothing, but there was always enough money to go to the opera. That was about the only thing we could afford. A ticket to the opera was only three rubles, and a loaf of bread on the black market was 300 rubles. So we spent a lot of time in the opera. And the sopranos and the tenors kind of silenced the growlings in our stomachs.

I remember my mother and father talking about the Germans before when there were rumbles of war. We weren’t too worried, per se, because they lived through the First World War, through Germany and Poland and so forth. And at the time the Germans were considered very civilized. So they weren’t too worried about it apparently.