Warszawa

Pronounced "Var-SHAH-vah" (English: Warsaw, German/Dutch: Warschau, Yiddish: וואַרשע / Varshe, Hebrew: וורשה, Russian/Ukrainian: Bаршава, Lithuanian: Varšuva, Hungarian: Varsó, Spanish/Latin: Varsovia)

The first Jews of Warsaw began settling in the city in the late 1300s and early 1400s CE. Throughout the Medieval period Jewish rights were severely restricted. For example, a “daily ticket” system allowed Jews to stay in the city for a maximum of 14 days.

By the mid-1700s the number of Jews in Warsaw had grown to about 2,500. After Jews were thrown out of the “New Jerusalem” neighborhood in 1777, they settled in an area west of town. The street called Jerusalem Avenues (Aleje Jerozolimskie) continues to serve as a major east-west thoroughfare in the city.

Warsaw was annexed to the Prussian (German) Empire in 1795 and fell under the power of the Russian Empire less than 20 years later in 1813. The Jewish community of Warsaw grew from about 6,750 in 1792 (10 percent of the total population) to 72,800 (one-third of the total population) in 1864. New synagogues built in 1802 and 1852, as well as the Great Synagogue built in 1878, began to offer services in the local languages of German and Polish. These moves ignited controversy with the traditional Orthodox community that opposed measures to assimilate into national culture.

By the 1880s two-thirds of the 300 synagogues in Warsaw were Hasidic, with a focus on traditional clothing and customs. Approximately 75 percent of Jewish children attended cheder, or Jewish elementary school. Throughout this time Jews could choose from a number of periodicals published in Yiddish, Hebrew and Polish. For example, the Hebrew language “Ha-Zefirah” magazine was founded in 1862.

Jews participated in both the 1830 and 1861 national uprisings against Russia, but continued to face discrimination and persecution from their neighbors. Two Jews were murdered in an 1881 pogrom.

After World War I (1914-1918) Poland was re-established as an independent country. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s the Jewish community was divided between traditional Orthodoxy, the Yiddish-speaking socialist movement, and Hebrew-nationalist Zionism—each with its own educational system. Survivor David Mitzner remembered that his high school “was based on the main language ’ivrit [Hebrew].” Survivor Leona Trachtenberg explained the diverse and multilingual Jewish culture saying, “Of course with her ‘Hebraist’ friends, Mother spoke Hebrew, with Jewish, [Yiddish].” Survivor Siegi Izakson added, “We all spoke German, and we spoke Polish, and we spoke Yiddish and we spoke Hebrew.”

During the decline of the economy of the 1920s and 1930s, Jews faced high levels of unemployment, and a number of Jewish aid organizations helped those in need. Survivor Miriam Brysk remembered that her father, a surgeon, “spent a lot of time treating the very poor Jews in Warsaw.” By 1939 Warsaw boasted 400 prayer houses to serve the more than 368,000 Jews who lived in the city (about 29 percent of the total population).

However, the Jewish population continued to face escalating antisemitic persecution. Trachtenberg recalled, “The Jews were looked down on, spat upon, terrorized by the Poles, called dirty ‘Yids.’” Survivor Jacob Gluckman added, “I was walking on a street and … I was beat up. I was beat up later in school too.” Despite this persecution, Survivor Siegi Izakson recalled, “For 17 years of my life, I received the attention and love of my parents, my grandparents, my family.”

The thriving Jewish culture of Warsaw was systematically destroyed after the German invasion of Poland in September 1939. Gluckman was standing in front of his family’s grocery store when “all of a sudden I see some planes in the sky,” realizing “Germany was bombing Warsaw.” Jews’ rights were curtailed and they were forced into the walled ghetto established in April 1940. Within the ghetto an average of 13 people lived inside a single room. Due to the spread of disease and famine caused by food rationing, more than 100,000 Jews had died in the ghetto by the summer of 1942.

Mass deportations to the Treblinka death camp began in July 1942, averaging approximately 6,000 Jews per day. Despite the inhumane conditions, a group of resistance fighters led an armed uprising that combatted Nazi forces for three weeks before the final liquidation of the ghetto in May 1943.

Warszawa: Photographs & Artifacts

-

Roman Vishniac photographed a vendor selling apples on Gęsia Street, one of the main thoroughfares in a Jewish neighborhood of Warsaw, ca. 1935-38. Holocaust Museum Houston Permanent Collection: 2015.001.005

Roman Vishniac photographed a vendor selling apples on Gęsia Street, one of the main thoroughfares in a Jewish neighborhood of Warsaw, ca. 1935-38. Holocaust Museum Houston Permanent Collection: 2015.001.005 -

In this photo by Roman Vishniac, members of Poland's right-wing nationalist party give the Nazi salute during an anti-Semitic demonstration, Jewish district of Warsaw, ca. 1937-38. Holocaust Museum Houston Permanent Collection: 2015.001.002

In this photo by Roman Vishniac, members of Poland's right-wing nationalist party give the Nazi salute during an anti-Semitic demonstration, Jewish district of Warsaw, ca. 1937-38. Holocaust Museum Houston Permanent Collection: 2015.001.002 -

Deportation of Jews to the Warsaw ghetto. Credit: Yad Vashem

Deportation of Jews to the Warsaw ghetto. Credit: Yad Vashem -

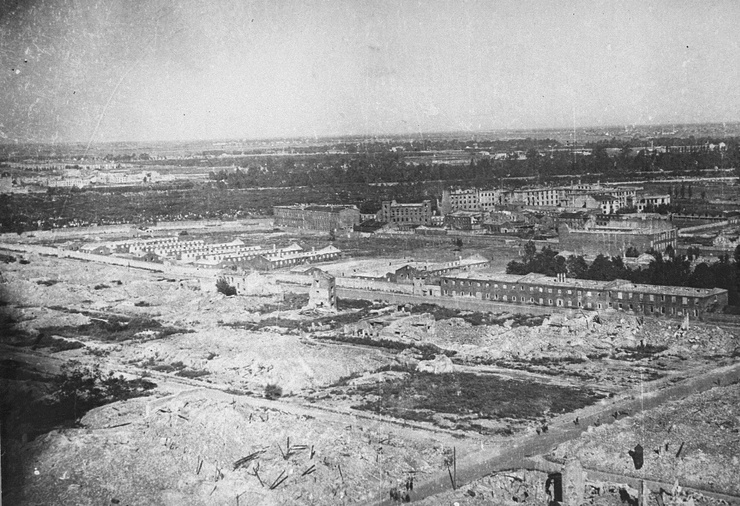

View of the ruins of the Warsaw ghetto. Pictured in the middle, surrounded by high wall with watchtowers, is the west side of the Gęsiówka prison. The Jewish cemetery on Okopowa Street is visible in the background on the left behind Gęsiówka concentration camp. Photo taken circa April-May 1945. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Juliusz Bogdan Deczkowski

View of the ruins of the Warsaw ghetto. Pictured in the middle, surrounded by high wall with watchtowers, is the west side of the Gęsiówka prison. The Jewish cemetery on Okopowa Street is visible in the background on the left behind Gęsiówka concentration camp. Photo taken circa April-May 1945. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Juliusz Bogdan Deczkowski -

The ruins of the Synagogue on Tłomackie street, May 16, 1943. Credit: Yad Vashem

The ruins of the Synagogue on Tłomackie street, May 16, 1943. Credit: Yad Vashem -

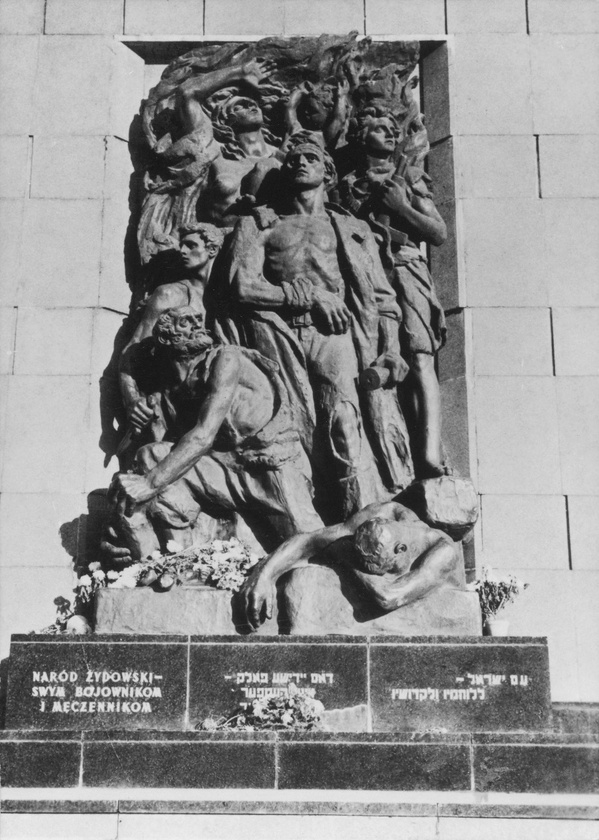

A memorial to the heroes of the Warsaw ghetto uprising by sculptor Nathan Rapaport, 1948. The monument was erected on the site of the destroyed ghetto. A copy of this monument is in Yad Vashem in Jerusalem. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Sylvia Kramarski Kolski

A memorial to the heroes of the Warsaw ghetto uprising by sculptor Nathan Rapaport, 1948. The monument was erected on the site of the destroyed ghetto. A copy of this monument is in Yad Vashem in Jerusalem. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Sylvia Kramarski Kolski -

The Jewish cemetery of Zduńska Wola was established in 1826. Today it is overgrown and neglected. © Hubert Śmietanka / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-SA-2.5

The Jewish cemetery of Zduńska Wola was established in 1826. Today it is overgrown and neglected. © Hubert Śmietanka / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-SA-2.5

Destroyed Communities Memorial Slope

Warszawa: Survivors

I remember, though, as the war started, the sounds of airplanes and bombs dropping. … I remember the fear, people running.

We just lived from day to day not knowing what would the next day bring. As soon as the city was cleaned up from the rubble, the Germans took upon themselves the job of persecuting the Jews. They wanted to make it understood that the Jewish people in Poland are not the same as their Polish neighbors. So day after day we used to get new proclamations which were posted on the walls with new orders.

"The whole family perished. I still don’t know how I survived myself."

The first thing that happened to us is that we lost our names. No longer were we individuals. Now we became numbers. Each of us received a number, and we were to remember this number, and eventually we sewed it on our jackets. Our hair was shaved off, and we were told that we are no longer human beings. We were now subhumans, and as such we will be treated. So it will be up to us to fall in line and accept the situation or, if we object, the end will be death, and they meant it.

I came to the conclusion that I was not a victim. I was a victor. I was able to beat the system. This gave me a good feeling. Ninety percent of my time was thinking and thinking and preparing for things that never happened. Frankly many times I was so tired of it… I asked myself, is this worth it?

I am glad to let the people know about my six years’ experience which I went through starting from the war which started September 1939.

Every day in the life of a person who lived in Warsaw is a day of long history. … Every minute was a day of survival.

The Jews were looked down on, spat upon, terrorized by the Poles, called dirty 'Yids.'