Zloczow

Pronounced "ZWOCH-oov" (Ukrainian: Zolochiv / Золочів, Russian: Zolochev / Золочев, Yiddish: זלאָטשאָוו / Zlochev, Hebrew: זלאטשוב)

The first known Jews of Złoczów established a small settlement in the town in the mid-1500s. In 1613 Jews received the rights to live and conduct trade in the city and constructed a small wooden synagogue. During this period the Jews of Złoczów faced no restrictions on where they were allowed to live or what jobs they could have—rare privileges for the time. Jews often worked as grain traders or sometimes as artisans in the glass industry or in saw mills. When the town synagogue burned down in 1727, the town’s Polish landowner contributed funds to rebuild it.

In 1772 the area became part of the Austrian Empire. This period was also marked by the growing popularity of the Hasidic movement among the Jewish community.

The arrival of railroad lines in the 1870s allowed many Jews the opportunity to work in the booming construction industry. A Jewish-owned printing house that started operations in 1870 would produce about 1,000 Polish-language books over the next four decades.

Throughout this time Jews made up about half the population of the town (roughly 5,000 of about 10,000 total residents) and two Jews were elected to serve in the Austrian parliament in Vienna. The thriving Jewish community included numerous cultural, charity and political organizations. For example, the Yad Haruzim (“Industrious Hand”) artisans group and a Jewish hospital opened in 1885. The town’s Zionist activity also grew from the late 1800s, as more and more Jews supported the creation of a Jewish state. In 1904, a modern cheder, or Jewish elementary school, opened. After a few years this school was united with the Zionist school and in 1912 began publication of “The Young Hebrew” periodical.

During World War I (1914-1918) the city was captured and held by the Russian army for one year, and many prominent Jewish and Polish citizens were sentenced to the interior of Russia. Many Jews also arrived in Złoczów seeking refuge from other war-torn areas. The Jewish community established an aid organization and soup kitchen to help refugees.

Violence continued even after the war ended in 1918 as Polish, Ukrainian and Soviet forces fought for control of the town after the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Jews found themselves the victims of robbery and violent attacks.

Still, the Jews of Złoczów managed to resume their lives after the town was established as part of the Republic of Poland in 1920. Jews owned a number of small businesses and were also active in the factory and agricultural industries. Jewish children usually attended one of the town’s Jewish schools, which included a dressmaking school and a number of Hebrew schools. Survivor Mela Zwecker remembered “joyous holidays filled with laughter, fun, and good food” and “birthday celebrations that made me feel very special.”

In 1935—two years after Hitler’s rise to power in Germany—antisemitic manifestos were distributed throughout the town, Jewish clerks were fired from their jobs, and a Jewish family was murdered in a nearby village. The next year witnessed a coup against the pro-Jewish Polish mayor of Złoczów, and the Jewish cemetery was desecrated.

At the start of World War II in September 1939 the city was occupied by the Soviet Union. Two years later, on the July 2, 1941 the German army invaded. Approximately 4,000 Jews were killed in a pogrom by their Ukrainian neighbors. Between August and November of 1942 approximately 5,200 Jews were sent to concentration camps. A Jewish ghetto was established in December 1942, and on April 2, 1943 its 6,000 remaining Jews were executed and buried in a mass grave. Although they had made up half of the city’s prewar population, the Jewish community of Złoczów was destroyed in less than two years.

Zloczow: Photographs & Artifacts

-

Interior view of the Złoczów synagogue, from the Brockhaus and Efron Jewish Encyclopedia (1906—1913). Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain (PD-RusEmpire)

Interior view of the Złoczów synagogue, from the Brockhaus and Efron Jewish Encyclopedia (1906—1913). Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain (PD-RusEmpire) -

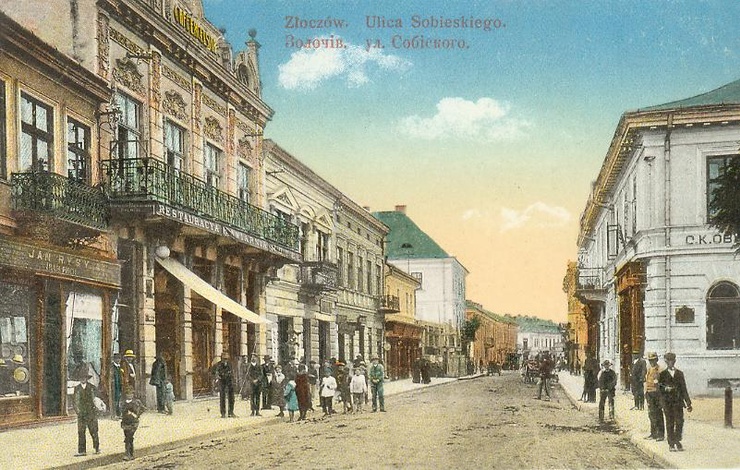

The postcard shows a view of Sobieski Street in Złoczów, 1916. Credit: Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain (PD-1996)

The postcard shows a view of Sobieski Street in Złoczów, 1916. Credit: Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain (PD-1996) -

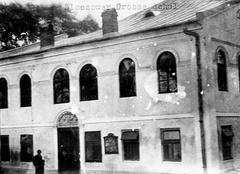

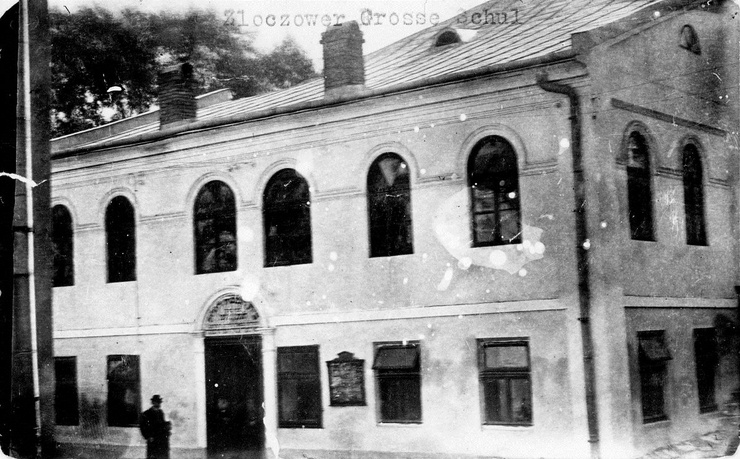

The Great Synagogue in Złoczów. Credit: Yad Vashem

The Great Synagogue in Złoczów. Credit: Yad Vashem -

A memorial in the former Jewish cemetery of Złoczów, July 2013. The text reads: "In the memory of the holy martyrs, Jews of Zolochev that were ruthlessly killed by the Nazi murderers during 1941-1945. Credit: sztetl.org.pl/Krzysztof Bielawski

A memorial in the former Jewish cemetery of Złoczów, July 2013. The text reads: "In the memory of the holy martyrs, Jews of Zolochev that were ruthlessly killed by the Nazi murderers during 1941-1945. Credit: sztetl.org.pl/Krzysztof Bielawski -

Memorial stone in the Bełżec extermination camp, July 2009. Credit: sztetl.org.pl/Adam Marczewski

Memorial stone in the Bełżec extermination camp, July 2009. Credit: sztetl.org.pl/Adam Marczewski

Destroyed Communities Memorial Slope

Zloczow: Survivors

Every new beginning is difficult, but particularly for someone who has just been through hell. Having no family, no roots, not knowing the language—but there was no time for pity when I came to America.