Lublin

Pronounced "LOOB-leen"

In 1336 Polish King Casimir the Great granted the first official privileges to the Jews of Lublin. Although Jews were required to live in the segregated Jewish Quarter, in 1453 they were granted the privilege of free trade and the city became a Jewish cultural and religious hub. In 1567 construction was completed on the grand Maharshal synagogue. A Hebrew printing press founded in 1578 continued to operate until the 1800s.

In the 1600s the Jews of Lublin faced harsh discrimination as trade was severely restricted and Jewish stores were subject to looting which periodically erupted into violence. In 1655 the city was captured by Cossacks and more than 2,000 Jewish residents were massacred.

More than one hundred years passed before the community re-established itself in the late 1700s. Jews contributed to the economy as tailors, furriers and jewelers, among other trades. In 1795 Lublin and the surrounding areas were annexed by the Austrian Empire, only to be turned over to the Russian Empire 20 years later in 1815. Jews finally received equal rights as citizens in 1862.

By 1897 Jews made up 48 percent of Lublin’s total population of 50,152 residents. This thriving Jewish community included a hospital, an orphanage, more than 40 Jewish schools and a number of cultural clubs. For example, the Zamir society promoted Hebrew literature and music and organized a drama circle.

When World War I started in 1914, Jewish property was looted and destroyed until the city was taken by the Austrian Empire one year later in 1915. During this time the first Jewish newspaper was established, as well as the first amateur Jewish theater and first Jewish public library. At the end of the war in 1918 Lublin briefly served as the seat of the new government of the independent country of Poland.

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s Jews continued to operate businesses and run small factories in Lublin, in addition to working in the town’s brewery, brickyard and various flour mills. Members of the Jewish community participated in groups such as trade unions and sports clubs and could worship in one of more than 100 synagogues and prayer houses in the city. Many families subscribed to one of three Yiddish-language newspapers and most Jewish children attended Jewish schools.

Survivor Ina Bernstein recalled that boys and girls attended separate schools. Her family lived in a Jewish neighborhood and were “very Orthodox.”

It was also during this time that antisemitism began to intensify across Europe, especially after Adolf Hitler was appointed Chancellor of Germany in January 1933. In 1936 the antisemitic Endek party of Poland organized a boycott of Jewish businesses and a number of tradesmen were violently attacked. Bernstein recounted how children would pull the beard and side curls of a poor Jewish man in her neighborhood, saying, “We were not Poles. We were Jews.”

The German army entered Lublin on September 18, 1939. Jewish property was confiscated and Jews were seized for forced labor in Nazi factories and farms. In March 1941 almost 40,000 Jews were forced into the Lublin ghetto and in October the Majdanek concentration camp opened on the outskirts of the city. In 1942 the 375-year-old Maharshal synagogue was blown up and the Lublin ghetto was liquidated. Of the approximately 40,000 Jews who lived in Lublin before World War II only about 1,200 (.03 percent) survived the Holocaust.

Lublin: Photographs & Artifacts

-

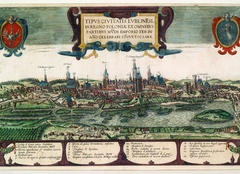

View of the city of Lublin in 1618. Wikimedia / Public Domain (PD-1996)

View of the city of Lublin in 1618. Wikimedia / Public Domain (PD-1996) -

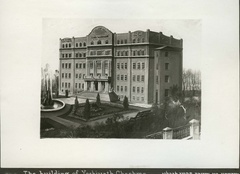

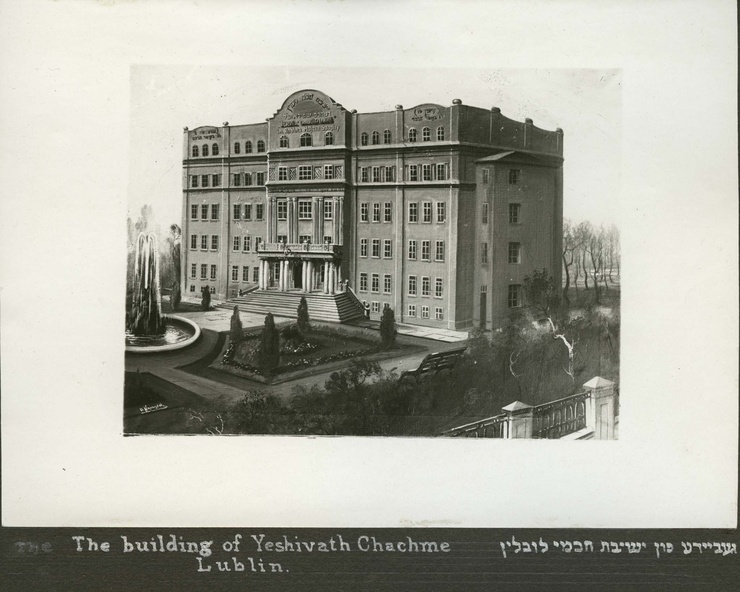

The building of the "Chachmey Lublin" Yeshiva. Credit: Yad Vashem, courtesy of Sara Rothner

The building of the "Chachmey Lublin" Yeshiva. Credit: Yad Vashem, courtesy of Sara Rothner -

View of the Jewish cemetery in Lublin. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Anonymous Donor

View of the Jewish cemetery in Lublin. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Anonymous Donor -

View of a street in the Lublin ghetto through an archway, Sep 1, 1939 - May 7, 1945. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Archiwum Dokumentacji Mechanicznej

View of a street in the Lublin ghetto through an archway, Sep 1, 1939 - May 7, 1945. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Archiwum Dokumentacji Mechanicznej -

Polish laborers cart away furniture and dismantle buildings after the liquidation of the Lublin ghetto, circa 1942. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Instytut Pamięci Narodowej

Polish laborers cart away furniture and dismantle buildings after the liquidation of the Lublin ghetto, circa 1942. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Instytut Pamięci Narodowej

Destroyed Communities Memorial Slope

Lublin: Survivors

No matter how old I am or what I went through, the shadows of my family are always with me and remain in my heart.

During the war in France I was in this apartment and we were so cold and I didn’t have any coal and I said to myself, ‘Oh, my G-d, I am cold. How about my parents in Poland?’ That’s what I was mostly concerned with. I wasn’t thinking of their safety. I was just thinking that they were cold.