Kaunas

Pronounced "Cow-nahs" (German: Kauen, Polish: Kowno, Russian: Kovno / Ковно, English: Kovno, Yiddish: Kovne / קאָװנע)

In the 1500s a Jewish community began to develop across the river from Kaunas in Slobodka (Vilijampolė in Lithuanian), which over the centuries evolved into the Jewish district of the city.

In 1795 the area around Kaunas was absorbed into the Russian Empire. Over the next few hundred years Jews faced numerous waves of persecution and expulsion, although they gradually won the rights to settle, do business and vote in the city. In 1858 living restrictions were finally eased enough that many Jews were able to move from Slobodka to newer parts of the city.

Throughout the industrial period of the 1800s, larger factories often refused to employ Jews. However, some Jewish merchants were able to earn livings in the agricultural, linen, and wood trades. A number of Jewish welfare organizations arose to assist those in need, including a hospital built in 1807.

Slobodka became a center of traditional Jewish education, with a number of yeshivas (schools to study Jewish religious texts) established. The Ohel Yaakov synagogue built in 1871 served as a venue for choir concerts attended by Jews and non-Jews alike.

By the early 1900s, Kaunas had become an important center of the General Union of Jewish Workers (Bund) and Jews played an active role in resistance against the Russian Empire. During World War I (1914-1918), the Jews of Kaunas were forcibly moved to the interior of Russia. After the German army captured Kaunas in September 1915, those Jews who returned to the city found their homes and businesses had been looted and destroyed.

In 1918 Lithuania was established as an independent country. That December, 22 Jews were elected to the 71-member Kaunas city council. From 1920 until 1939, Kaunas served as the temporary capital of Lithuania, increasing the city’s stature and encouraging Jewish immigration.

Jewish community institutions included the Avraham Mapu Library (opened in 1908), the “Yidishe Shtime” daily newspaper (founded in 1919), two theaters and a number of schools that ranged from elementary education to vocational training. The Bikkur Holim hospital was one of the largest in Lithuania.

In 1923, the 25,044 Jews of Kaunas made up more than 25 percent of the city’s population. Survivor Issa Selig recalled, “Kovno was a very nice city. It was a very cultured city for the small place that it was.”

Survivor Sonia Stern remembered that her “very religious” family followed traditional Orthodox customs. She described the significance of the holidays, saying “Oh, that was the most beautiful thing. All the holidays were special for us kids.” Stern added, “For Passover Seder, maybe around 40 to 50 people used to get together… and the singing.”

The 1930s saw a rise in anti-Jewish measures as the Nazi party gained influence across Europe. Jewish businesses faced boycotts, university students were segregated and kosher butchers and Hebrew signs were banned. Stern recalled, “I remember being a child, name calling and beating up Jewish kids in the schools.” However, she added that her family also “had non-Jewish friends, non-Jewish neighbors. Life wasn’t bad till the war.”

Beginning in 1940, the Jewish community of Kaunas was quashed under Soviet occupation. Businesses were nationalized, Jewish activities were banned, and Jews were subject to arrest and exile.

Although some organizations managed to exist underground for a short time, the Jewish community of Kaunas was systematically destroyed after the Nazi invasion of July 1941. Half the city’s approximately 40,000 Jews were murdered within six months. The rest were forced into a ghetto in the old Jewish district of Slobodka. Only about 3,000 Jews from Kaunas survived the Holocaust.

Kaunas: Photographs & Artifacts

-

Exterior of a synagogue in Kaunas. Credit: Yad Vashem

Exterior of a synagogue in Kaunas. Credit: Yad Vashem -

View of the Kovno (Kaunas) Jewish cemetery with the tombstone of Rabbi Isaac Elhanan Spektor. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Shmuel Elhanan

View of the Kovno (Kaunas) Jewish cemetery with the tombstone of Rabbi Isaac Elhanan Spektor. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Shmuel Elhanan -

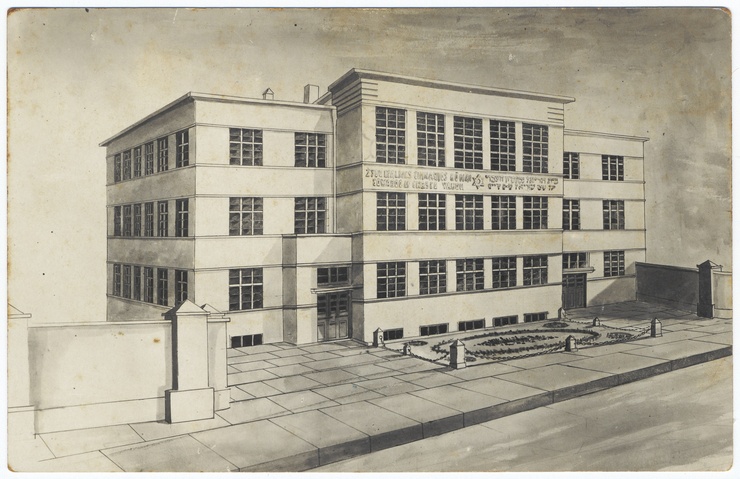

Exterior view of the Real Hebrew Gymnasium in Kaunas, circa 1930-1935. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Alexander Zeidel

Exterior view of the Real Hebrew Gymnasium in Kaunas, circa 1930-1935. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Alexander Zeidel -

Russian tanks roll through the streets of Kaunas during the Soviet occupation of Lithuania, June 15, 1940. This photo was taken through a hole in a piece of paper that was used to cover a window. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of George Birman

Russian tanks roll through the streets of Kaunas during the Soviet occupation of Lithuania, June 15, 1940. This photo was taken through a hole in a piece of paper that was used to cover a window. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of George Birman -

Burnt and destroyed houses in the Kaunas ghetto. Credit: Yad Vashem

Burnt and destroyed houses in the Kaunas ghetto. Credit: Yad Vashem

Destroyed Communities Memorial Slope

Kaunas: Survivors

I clearly remember going with my mother in 1945 or ’46 after the war to places where the Red Cross had lists of survivors, and I remember my mother looking at the lists. I remember the tears rolling down her cheeks when she couldn’t find anyone.

I did have a wonderful childhood. It didn’t last long, but it was wonderful while it lasted.

My children know everything, everything. They made peace with it, but they were very angry when they were younger. I know they suffered a lot because of the Holocaust. Not only me, not only us, but them too.