Thessaloniki

Greek: Θεσσαλονίκη (also called Thessalonica or Salonica in English)

The first Jewish community in Thessaloniki was founded as early as 140 BCE by Jews from Alexandria (in present-day Egypt). The Roman Empire granted the Jewish community autonomy, or self-rule, which allowed Jews to take advantage of their location near the city’s port to develop strong commercial ties with many different parts of the world. These Romaniote Jews spoke Greek and often adopted Greek versions of their names.

Despite periodic waves of persecution, the community managed to survive and grow over the next thousand years. In 1430 the city fell to the Ottoman Empire (modern-day Turkey). Large numbers of Jews continued to arrive in Thessaloniki, especially after the 1492 expulsion of all Jews from Spain. These Sephardi Jews spoke Ladino, a form of Medieval Spanish written in Hebrew.

A series of devastating fires in 1543, 1545 and 1548 threatened the livelihoods of the Jewish community, however a portion continued to thrive as merchants. During the late 1500s Thessaloniki established its place as a center of Jewish learning, and hosted a variety of leading rabbis.

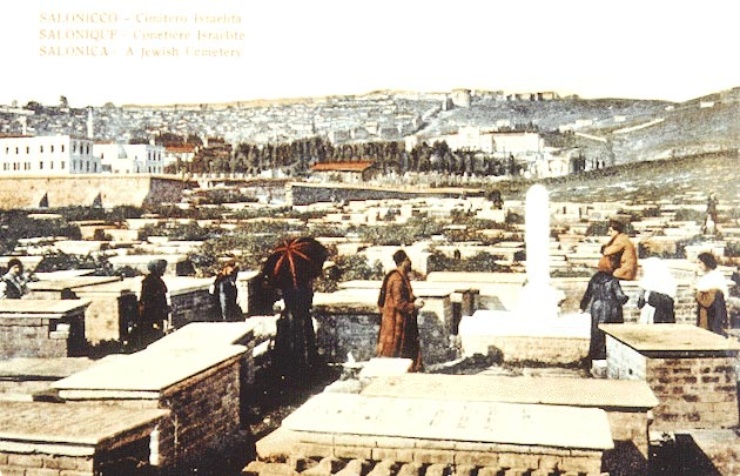

Throughout the 1600s the more than 30 Jewish congregations of Thessaloniki each maintained community institutions such as burial societies, hospitals, and schools. In 1680 all the congregations merged into one united organization. Despite another series of fires, the Jewish merchant population continued to flourish, as did a number of Jews who worked in the tobacco industry.

The late 1800s and early 1900s were considered a “Golden Era” for the Jewish culture of Thessaloniki. During this time many Zionist organizations took root in the community and began to advocate for the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine.

By 1900, the approximately 80,000 Jews of Thessaloniki made up nearly half of the city’s total population of 173,000. In addition to their traditional role as merchants, many Jews worked as lawyers, doctors, teachers and dock workers. In 1912 Thessaloniki was liberated by the Greek army and the Jewish population finally received the same rights as all other Greek citizens.

These advances would prove to be short-lived as antisemitism gained support across Europe in the 1920s and 1930s. A series of 1922 laws prohibited any inhabitants of Thessaloniki from working on Sundays, harming Jewish businesses. In 1932 the entire Jewish neighborhood of Thessaloniki was burned to the ground and many Jewish residents of the city emigrated to Palestine. Despite continued persecution, the Jewish community managed to maintain a strong economic position working in a variety of professions.

Survivor Charles Molho remembered that his father, a banker, “died when I was five years old,” leaving his mother to provide for the family of six. Molho recalled she “was a seamstress, one of the best in Salonica.” After Charles and his siblings attended the local Italian Catholic schools, he opened a lumber company with his brother. Tragically, following the Italian invasion of Greece in October 1940 Molho’s brother “went voluntarily to the Greek army” and was killed that December.

In the spring of 1941 the city was occupied by Nazi forces, leading to the immediate and systematic persecution of the Jewish population. All Jewish-owned property and homes were confiscated by the German army, including the lumber factory where Molho worked.

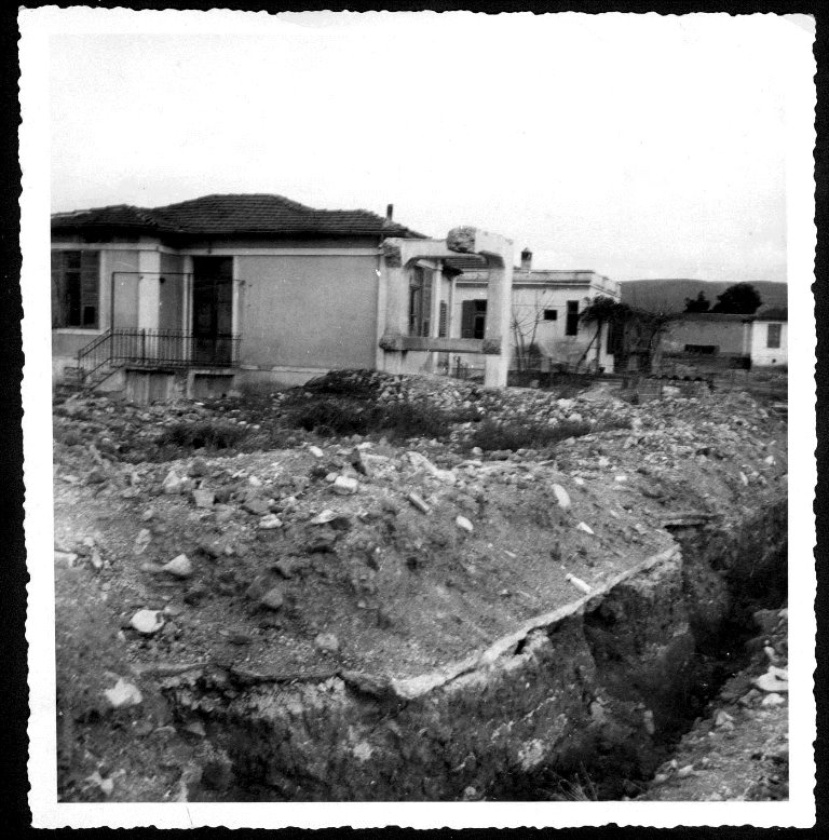

In 1942 Nazi forces destroyed the Jewish cemetery that had served the community since the 1400s. Jews were forced into ghettos, and by August of 1943 more than 56,000 Jews had been deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau, including Molho and his new wife. Of the 60,000 Jews who lived in Thessaloniki in 1935, only 1,950 would return to the city. The 2,000-year-old community had been destroyed.